University of Cincinnati Integrative Health Learning Collaborative Case

The Integrative Health Learning Collaborative sought to improve the delivery of whole-person care and make integrative health routine and regular in primary care. During the learning collaborative, UC Health at the University of Cincinnati brought more integrative health into group visits, improved the curriculum and process and increased collaboration within UC Health.

Six in 10 adults in the U.S. have at least one chronic disease, and four in 10 have two or more, according to the CDC.1 People in underserved communities bear far more of the burden of chronic disease than people in more affluent communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized these health and health care disparities. More people in underserved communities, especially those from racial and ethnic minority groups, got sick or dyed or were at higher risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19 compared to the general population.

Even before the pandemic, primary care providers struggled to find the time, tools and resources to help patients with chronic diseases—whether affluent or underserved—improve their health and wellbeing. Yet, most chronic diseases seen in primary care can be prevented, managed or even reversed by addressing their underlying social and behavioral determinants.

BETTER WAY TO MANAGE CHRONIC DISEASE

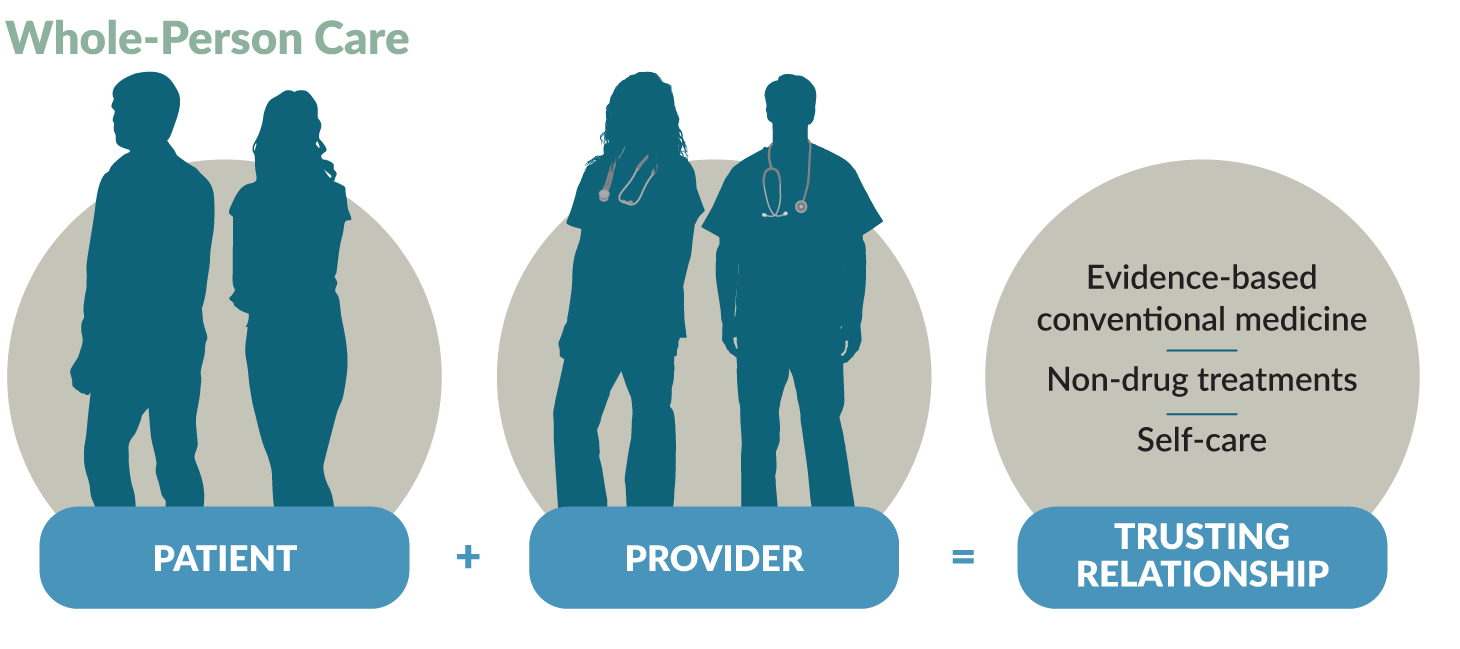

Whole-person care and integrative health focus on helping patients achieve health and wellbeing, not just on the treatment of disease, illness and injury. It is a better way to manage chronic disease because it addresses all the factors that impact health and healing:

- Medical treatment

- Mental health

- Personal behaviors and lifestyle

- Social determinants of health

- Personal determinants of healing

Integrative primary care providers use all proven approaches:

- Evidence-based conventional medicine

- Non-drug treatments (including complementary and alternative medicine)

- Self-care

They focus on what matters most to each person and establish trusting, ongoing relationships to help patients heal.

Whole-Person Care

Helps patients achieve health and wellbeing:

Integrative primary care providers use a person-centered, relationship-based approach to integrate self-care with evidence-based conventional medicine and non-drug treatments. They consider all factors that influence healing:

- Medical treatment

- Mental health

- Personal behaviors and lifestyle

- Social determinants of health

- Personal determinants of healing

Uses proven approaches:

Integrative primary care providers coordinate the delivery of evidence-based conventional medicine and non-drug treatments and self-care:

- Conventional medicine is the delivery of evidence-based approaches for disease prevention and treatment currently taught, delivered and paid for by the mainstream health care system.

- Non-drug treatments focus on non-pharmacological approaches to care and include what is sometimes called complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

- Self-care is all the evidence-based approaches that individuals can engage in to care for their own health and wellbeing. Self-care promotes healthy behaviors and a healthy lifestyle to enhance health and healing. Approaches focus on the connection between the body, the mind the spirit and behavior, and cover food, movement, sleep, stress, substance use and more. Improving one area can influence the others and benefit overall health.

Goes beyond the doctor’s office to consider context:

Whole-person care is framed by each person’s social and personal context:

- Social determinants of health are the conditions in the places where people live, learn, work and play that affect health and quality of life.

- Personal determinants of healing are those personal factors which influence and promote health and healing. These include the physical, environmental, lifestyle, social, emotional, mental and spiritual dimensions which are connected and must be balanced for a happy and fulfilled life.

- Health Coaching is a delivery method for whole-person care. Health coaches use their expertise in human behavior to help individuals set and achieve health goals. They are an increasingly important component of whole-person care teams.

Providers work with patients to create a personalized health plan based on the person’s needs and preferences. To do this, they use free tools such as:

- The PHI (Personal Health Inventory), which assesses the person’s meaning and purpose in life, current health and readiness for change. Patients complete this before or during a primary care visit that integrates health and wellbeing.

- The HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note, a patient-guided process to identify the person’s values and goals in life and for healing so the provider can assist them in meeting those goals with evidence and other support.

Whole-Person Care Works

Evidence shows that whole-person care is effective in meeting the quadruple aim of:

- Better outcomes

- Improved patient experience

- Lower costs

- Improved clinician experience

Read more about the evidence supporting whole-person care.

THE INTEGRATIVE HEALTH LEARNING COLLABORATIVE

The Integrative Health Learning Collaborative sought to better manage chronic disease by addressing social and behavioral determinants of health to:

- Improve the delivery of whole-person care

- Make integrative health routine and regular in primary care

Seventeen clinics participated in the learning collaborative, held from October 2020 to September 2021. The Family Medicine Education Consortium and Samueli Integrative Health Programs sponsored the learning collaborative, which was funded by a grant from The Samueli Foundation.

Read more about the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative.

UC Health, the health system of the University of Cincinnati, is an integrated health system and Cincinnati’s only academic medical center. It includes:

- University of Cincinnati Medical Center

- West Chester Hospital

- Daniel Drake Center for Post-Acute Care

- UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute

- Lindner Center of HOPE

- Bridgeway Pointe

- University of Cincinnati Physicians, an 800-plus physician group

UC Health has 19 primary care clinics, 27 specialty ambulatory clinics, and more than 800 physicians and advanced practice providers.

Internal medicine faculty and residents care for an urban population with a high proportion of medically and socially-complex patients of all ages through three primary care practices at UC Health. Most of these patients are on Medicaid, while some are insured by Medicare or dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. Six to nine providers handle 1,200 to 1,400 patient visits each month.

CENTERING GROUP VISITS

In 2010, UC Health implemented Centering Group Visits to improve patient health and wellbeing. Centering Group Visits are a type of group visit that is standardized and patient-centered, and must adhere to strict national guidelines. Tiffiny Diers, MD, and Jinda Bowerman, DNP, run the centering program. Dr. Diers is Associate Professor and Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program at the University of Cincinnati and Centering Program Director at UC Health. Dr. Bowerman is a family nurse practitioner and co-director of the Centering Program at UC Health.

“The focus is on the patients as experts in their own lived experience and healing agents within their own lives and in the community, not about us as providers coming in as

experts and telling them what they have to do.”

Group learning based on the patients’ experiences improves equity. “Patients identify new angles for their health management that we as providers in many cases wouldn’t have thought of because our context is so different,” says Dr. Bowerman.

Evidence shows that Centering Group Visits improve patient outcomes and the experiences of patients. The literature on Centering Group Visits for pregnancy, for example, shows reduction in preterm birth rates and increases in breast feeding, according to the Centering Healthcare Institute.2 Centering Group Visits lead to more patient engagement, learning and self-confidence.2

Centering Group Visits benefit providers too. They give providers more time to spend with patients and reduce the repetition of information.

“We really get to look at and hear about what really matters to the patient and move forward in addressing their health goals in a realistic way.”

Initially, the Centering Group Visits at UC Health focused on pregnancy and then parenting. The team added Centering Group Visits for chronic conditions—chronic pain, weight management (obesity) and diabetes.

Format and types of Centering Group Visits

Centering Group Visits last about two hours, usually include 6 to 10 patients and have three key components:

- Health assessment:

- Each patient completes a health assessment and has a brief assessment with a licensed medical provider. This makes group visits billable.

- Interactive learning on topics tailored to the group’s interests and needs:

- Engaging activities and facilitated discussions where patients learn from each other and from providers and providers learn from patients.

- Activities focus on empowering patients and engaging them in a deeper and more meaningful way than traditional medical care.

- Community building:

- Patients are comforted by knowing they are not alone.

- Group care lessens feelings of isolation and stress while enabling patients to make friends and get support.

The table shows the structure of a typical group visit session at UC Health.

A Sample In-Person Centering Group Visit Plan

| Centering Group Visit Sample In-Person Visit Plan | |

|---|---|

| Pre-Visit (30min) | Intake, vitals, 1:1 time with providers. |

| Welcome and Opener (15min) |

Welcome and review of group guidelines Opener: What’s your name and something that you are grateful for? |

| Activity 1 (25min) | Sleep tile game: Strategies for healthy sleep are put on papers arranged in a circle. Patients go to a “tile” showing a strategy they have used successfully. Group sharing occurs. Then patients move to a tile showing a strategy they would like to try. |

| Break (20min) | Socializing, complete 1:1 time with providers |

| Activity 2 (25min) | Body scan meditation |

| Goal Setting (20min) | Reflection and Goal Setting |

| Closing (15min) | Facilitators ask “What did you learn today?” or “How will you use your new skills when you leave?” Inspirational Quote or Affirmation |

UC Health has basic and advanced Centering Group Visits. Basic Centering Group Visits last four months, with one meeting per month. Each session follows the same outline.

Advanced Centering Group Visits also meet monthly but are ongoing. People attend as frequently or infrequently as they want to. Topics are driven by group suggestions. The results section of this case study highlights changes to advanced Centering Group Visits made as a result of participating in the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative.

Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman were ready to expand Centering Group Visits when the COVID-19 pandemic occurred. They had to switch to virtual group visits, using Microsoft Teams. This was difficult for many patients, who had technology issues ranging from not having a device to use to not knowing how to connect for a virtual meeting or how to use the technology. Also, providers had to do the assessments by telephone before each Centering Group Visit.

“Virtual groups are successful once you get through challenges of bridging the digital divide and the technological hassle of getting patients on,” says Dr. Bowerman.

While Centering Group Visits are integrative by their nature, UC Health wanted to add more integrative health structure and principles to the visits and to their primary care practice. The Integrative Health Learning Collaborative provided a way for them to do this.

During the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative, UC Health brought more integrative health structure and services into group visits. The work focused on the advanced centering groups for patients with chronic pain, obesity or diabetes, where the curriculum was less well developed than the curriculum for the basic centering groups.

THE INTEGRATIVE HEALTH TEAM

The Integrative Health Learning Collaborative team consisted primarily of the “dynamic duo” of Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman. Initially, they had planned to have a larger team, including other physicians, residents, support staff, and quality improvement and data personnel. However, key program leaders and staff left UC Health before the project started. Also, residents and other staff were diverted to handling patients with COVID-19.

“We had envisioned our role being directing the improvement work, curriculum redesign to incorporate Integrative Health Learning Collaborative topics within Centering Group Visits and doing some work with patients on how best to incorporate these changes,” says Diers. “We ended up having to do more of the staff roles. Anything that didn’t absolutely have to get done in order for things to proceed didn’t get done. We’re lucky to have been able to move forward.”

Patient Case: Lifestyle and Mindset Changes Lead to Better Health

John [not his real name] is a 54-year-old with chronic kidney disease, hypertension, hypersensitivity lung disease and depression. In 2017, he was treated for a middle cerebral artery aneurysm. In May 2020, John was admitted to UC Health with diabetic ketoacidosis. His HbA1c had increased from 6.5 to 11.3. John also had chronic low back pain.

In the hospital, John received insulin. A diabetes educator visited John, who was also referred to The Hoxworth Center at UC Health for primary care invited to join the Basic Centering Diabetes Group. John began attending the group in July 2020 and graduated four months later in October. Then he began attending the Advanced Centering Diabetes and Healthy Lifestyles Group. In January 2021, he began the HOPE Note process in that same group.

Through the Advanced Centering Diabetes and Healthy Lifestyles Group, and the HOPE Note process, John is actively working on lifestyle changes. He is walking every day and eating more fruits and vegetables. Also, John has stopped consuming sugary drinks.

John was able to stop using insulin and is now just on metformin. His blood pressure is controlled. After recognizing some cognitive concerns, providers set him up with a mediset and medication app to help with medication safety and sent him for neuropsychological testing. John is taking his other medications as directed.

“Now I know my mindset is one of the most important things about becoming healthy and that my mental health and physical health are connected,” says John.

Providers also noticed problems with sleep and sent John for evaluation. He was diagnosed with sleep apnea and is now using a CPAP machine. This has improved John’s energy and he is ready to try acupuncture and massage for his chronic lower back pain. He continues to see a therapist for depression.

John has made friends with other people in the group and feels supported because “they are going through the same things that I am.”

EVALUATING WHOLE-PERSON CARE

UC Health evaluated its use of integrative health for practice and clinical improvement. They used the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle and the McKinsey 7S model of change management to plan and manage implementation and to evaluate their changes and plan next steps to expand the delivery of integrative health.

Read more about PDSA cycles and the McKinsey 7S model of change management.

Here is what UC Health did.

A More Comprehensive Evaluation

Since UC Health has been involved with many quality improvement projects and learning collaboratives, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman have substantial experience with practice change methods. They use the Model for Improvement, which focuses on accelerated change and uses the PDSA cycle.

They started with a key driver diagram, which showed:

- The project aims

- The population

- Primary drivers that contribute directly to achieving the aims

- Secondary drivers

- Interventions, or changes, to test.

Using the key driver diagram as a guide, they then conducted several PDSA cycles of small tests of change in essential areas.

The Integrative Health Learning Collaborative, however, required the painstaking collection of data that was not automated and tools that were not integrated into Epic. During COVID-19, the coordinator of the Centering Group Visits program left and finding a replacement took several months. With less support from quality improvement and data personnel staff than expected, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman were unable to keep up with data collection and analysis, which limited the ability to collect quantitative data.

CLINIC HIGHLIGHTS

Despite the challenges, UC Health reported the following accomplishments related to integrative health.

The learning collaborative team added integrative health to advanced centering groups.

Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman incorporated the PHI, the HOPE Note and integrative health activities into Advanced Centering Group Visits for patients with chronic pain, obesity and diabetes who had completed a basic centering group. They developed a process to incorporate segments of the PHI during the medical assessment before group visits and taught residents how to do this. The segment of the PHI used for each visit was based on the topic for the group visit.

Residents diverted to caring for patients with COVID-19 were unable to participate in the project until Spring 2021. Sometimes it was difficult for Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman to complete the PHI segment also. Doing the PHI in segments was helpful for patients but less helpful for providers in measuring the patients’ progress or the impact of the advanced Centering Group Visits.

“It would be cleaner if, for example, if we had an individual HOPE encounter at the start of each centering cohort and completed the PHI to create a starting integrative health plan,” says Dr. Diers. Lack of time, however, is a barrier to doing this.

“I decided to try what worked for other people so I tried the yoga we learned and sleeping with body pillows. I have gone from taking one pain pill every day to only taking two pills since last [month’s] visit.”

HOPE topics and activities added to the advanced Centering Group Visits included:

- Fiber Fun with a registered dietician

- Chair and balance exercises with an exercise therapist

- A nature and health art activity

Adding integrative health changed the conversation with patients during Centering Group Visits.

Advanced Centering Group Visits now focus more on social support, physical environment and what matters most to patients.

“This was a great experience. It changed conversation with patients, especially around social support, the impact of the physical environment on health and the importance of

purpose and meaning on health.”

While all group visits naturally provide social support, the Advanced Centering Group Visits had not explicitly addressed social support. By focusing more on social support, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman learned that many patients lack social support. Some patients, especially those with chronic pain, have social support but family and friends don’t understand their pain. Now Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman highlight the importance of social support to health and how patients can seek out and strengthen supportive relationships.

“Before I would ask how things were going in your life at the end of the conversation. Now I do that first.”

The curriculum for the Advanced Centering Groups had focused on lifestyle: diet, exercise, sleep and stress management. During the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman also added content on the environment (neighborhood and home) and the purpose and meaning of life.

The learning collaborative team reassessed Centering Group Visits and re-designed the advanced centering group curriculum.

Integrative health activities incorporated into advanced Centering Group Visits will be further developed and used in both basic and advanced groups.

Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman would like to introduce patients to many different integrative health therapies in the Centering Group Visits. Patients will gain some basic self-care skills and will be able to decide if they want to pursue specific integrative health therapies. Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman will be using materials from the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative and bringing in integrative health practitioners as guest speakers.

Along with more focus on integrative health, changes to the advanced centering group curriculum includes a four-month structure and more check-ins between the monthly group visits. Both of these changes facilitate accountability and momentum, which Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman learned are important in behavior change during the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative. They introduced the new curriculum in November 2021.

Leaders of the Centering Group Visit program are building an integrative health community within UC Health.

Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman have been building relationships with “other like-minded practitioners” at UC Health’s Center for Integrative Health and Wellness. They are meeting experts who can serve as guest speakers during group visits and have learned about mind-body therapies that are available to their patients at no cost through philanthropic donations.

Also, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman are negotiating to locate the Centering Group Visit program within the Center for Integrative Health and Wellness (as of November 2021).

Qualitative evaluation results are being used to improve integrative health during Centering Group Visits.

The evaluation showed results of using segments of the PHI, HOPE activities, monthly goal-setting and problems in adding integrative health to Epic. Sample results include:

- Lifestyle segment of the PHI:

- Sleep was a common problem and patients need more time to discuss this. Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman added sleep to the template for Centering Group Visits.

- HOPE activities:

- Patients enjoyed doing a forest video meditation and drawing how they interact with nature. If there is time, the forest video meditation and the nature drawing could be separated into two activities.

- Monthly goal setting:

- Time sometimes ran short to do this at the end of the group, so goals were not SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-based). Also, it was difficult to get goals off of paper for tracking. In later Centering Group Visits, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman tried other ways to record goals, including in Epic and in PowerPoint slides.

The quantitative results are limited due to lack of staff support for data collection and analysis. As of June 2021, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman reported:

- 2 completed PHIs out of 30

- 0 completed PROMISs

- 26 HOPE activities completed out of 28 planned

- 0 patients with an integrative health plan

As of January 2022, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman were continuing data collection and analysis.

LEARNING COLLABORATIVE HIGHLIGHTS

UC Health reported the following benefits of participating in the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative.

Leaders of the Centering Group Visit program stayed focused on integrative health during a challenging time.

The COVID-19 pandemic and loss of key staff made it very difficult for Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman to move forward with integrative health. The structure provided by the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative and the support of faculty and other participants was key to making progress.

“This community has been invaluable in keeping us focused and inspired to continue working on making integrative health accessible and routine for our patients in primary care”

Connecting with other providers doing and interested in integrative health was inspirational and educational.

“I’ve enjoyed being able to meet with like-minded folks across the country and see some of the amazing options that other groups are providing in integrative health in a primary care setting,” says Dr. Bowerman. She and Dr. Diers were also inspired to look for and build connections with integrative health providers at UC Health.

Patients participating in Centering Group Visits are benefitting from the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative’s resources.

Throughout the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative, faculty and the clinics shared resources on many different integrative health therapies. Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman are using these in their group visits.

Key Insights for Implementing Integrative Health

Introduce integrative health at meetings with a short meditation or stretch. Learning collaborative meetings began with a short deep-breathing technique or meditation. Dr. Bowerman now leads colleagues in a short meditation or stretch at the beginning of meetings. Along with helping busy providers refocus and slow down, this is a nice introduction to integrative health.

Use group visits to bring integrative health to patients. Group visits, whether they are Centering Group Visits or other group visits, are a great way to bring integrative health to more patients. Integrative health topics and tools fit easily into group visits, which are naturally somewhat integrative in many ways. “With the group, you get an added level of wisdom of the lived experience for group learning and problem-solving, a supportive community and accountability,” says Dr. Diers.

When starting group visits, invest in developing facilitation skills, which drives outcomes, and use a proven model.

- Learn more about group visits: Chronic Disease Management with Group Visits (PDF), a case study on how to promote healthy behaviors among patients with chronic diseases

Complete training in and personally use integrative health or medicine. Dr. Diers completed training in integrative medicine and began adopting healthier behaviors. This helped her understand the large gap between learning and doing. “Translating information into action is the hard part, not getting the information into patients’ heads,” she says. Providers who create new lifestyle habits and mindsets will empathize with patients who are trying to do this.

Look for partners within your clinic or community. Partnering with others helps providers who are new to integrative health learn more about integrative health therapies and resources and can provide sources for referrals to lessen the load. By partnering with UC Health’s Center for Integrative Health and Wellness, for example, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman have met experts who can serve as guest speakers during group visits and learned about therapies that are available to their patients.

Loss of staff made adding integrative health to the Centering Group Visit program difficult. Key Centering Group Visit program staff left UC Health before the project started and residents and other staff were diverted to handling patients with COVID-19. Instead of having a team, Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman had to do most of the work themselves. They were not able to accomplish as much as they had planned during the learning collaborative.

The group visit format makes it difficult to complete the PHI. Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman were doing segments of the PHI before each group visit. Sometimes, however, they did not even have time to do this. One solution would be to do an introductory session to Centering Group Visits and complete the PHI as part of this. Lack of time, however, is also a barrier to doing this.

UC Health will continue to use integrative health in Centering Group Visits, add more experts and services in both the basic and advanced group visits, assess this work and make improvements.

Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman are also bringing integrative health to two other learning collaboratives and to two new types of patient visits at UC Health. The learning collaboratives focus on diabetes outcomes in the Medicaid population in Ohio and control of hypertension among black people in Ohio.

UC Health is launching cancer wellness group visits for breast and gynecological cancer survivors and brain health group visits for people with cognitive disorders and their caregivers. Dr. Diers and Dr. Bowerman are partnering with the providers to use an integrative health approach in these group visits.

A SYSTEMS-LEVEL APPROACH TO INTEGRATIVE HEALTH

Leadership changes at UC Health, including a new chair of internal medicine and the re-design of ambulatory care, provide an opportunity to use a systems-level approach to expanding integrative health. Wayne Jonas, MD, one of the leaders of the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative and Executive Director of Samueli Foundation’s Integrative Health Programs, is consulting on this with Dr. Diers, Dr. Bowerman and others at UC Health.

Evidence from existing whole-person care supports the effectiveness of this model in meeting the quadruple aim:

- Better Outcomes

- Improved Patient Experience

- Lower Costs

- Improved Clinician Experience.

This evidence includes a narrative review of several models of whole-person care and studies illustrate the business case for whole-person models in primary care2 and the models and studies cited in this section.

BETTER OUTCOMES

Whole-person care:

- Increases the ability to manage chronic pain and decreases opioid doses.4

- Improves patient-reported health and wellbeing.5

- Lowers A1c in people with diabetes.6

- Improves medication adherence.7

- Facilitates a healthier lifestyle.8

- Reduces the severity of heart disease.9, 10

- Reduces loneliness among seniors.11

- Lessens symptoms, including pain, depression, low back pain and headaches.12, 13, 14

IMPROVED PATIENT EXPERIENCE

Whole-person care:

LOWER COSTS

IMPROVED CLINICIAN EXPERIENCE

THE PDSA CYCLE

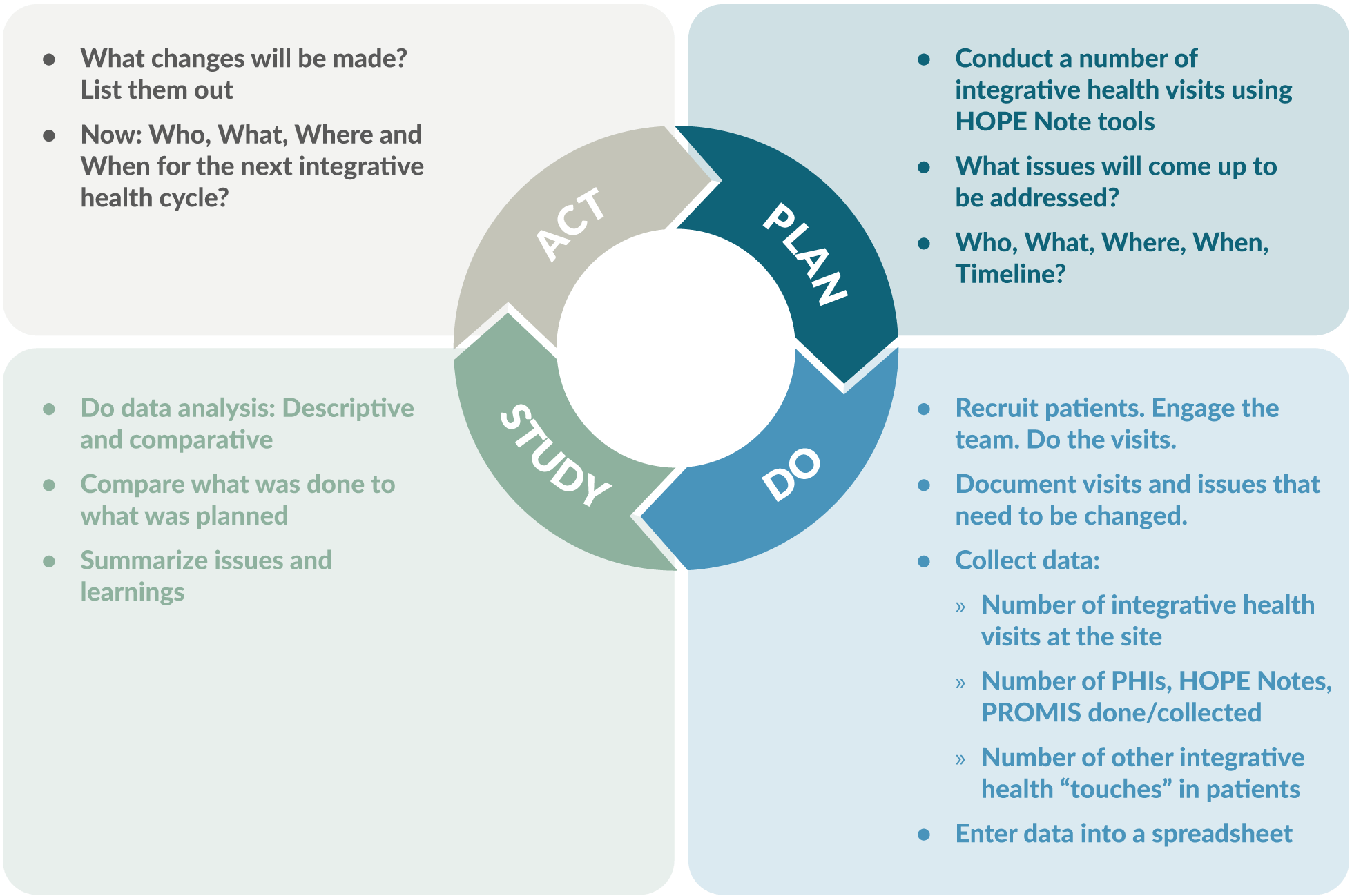

The PDSA cycle is a tool for documenting change. Clinics participating in the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative planned and tested small changes, learned from the results, and modified the changes as necessary.

PDSA Cycle

Source: Slide 9, PDSA and 7S Report Outs v1

THE MCKINSEY 7S MODEL OF CHANGE MANAGEMENT

The McKinsey 7S model of change management is a good way to plan and manage implementation of integrative health. The model considers three structural elements: strategy, systems and structure. It also recognizes three “people” elements needed to win the hearts of everyone from front office staff

to the most senior physicians. These include addressing the types of people who are going to lead the change, the skills of the people who will be involved, and the overarching leadership style within the organization. These elements are fuzzier, more intangible, are influenced by corporate culture and are sometimes more difficult to address.

The McKinsey 7S Model of Change Management

Graphic CC-BY 2.5 Wikimedia

Managing change by addressing all these barriers leads to the 7th “S,” creation of shared values underpinning the culture of the group.

Structural and People Elements in the McKinsey 7S Model of Change Management

| Structural Elements: | |

|---|---|

| Strategy: | What do you want to do differently? What will it replace? |

| Systems: | What changes in workflow needs to happen to do the new thing? |

| Structure: | How are you going to set up a new system to kick off and then monitor the initiative? |

| People Elements: | |

| Style: | How are you going to lead the change? |

| Staff: | Who can you enlist who will make it happen? Who do others in your practice look to for guidance? |

| Skills: | Who needs to be trained in the new workflow? What is the training? How can you give them ownership? |

Addressing all these issues through careful planning will lead to development of the shared values, the commonly accepted standards and norms within the practice that will make the switch to whole-person care a success.

USING THE 7S MODEL TO PLAN IMPLEMENTATION

Substantial planning is necessary to make the change to whole-person care.

Strategy: The obvious changes, as part of this initiative, are to start using the PHI, start conducting integrative visits around the HOPE note, and start setting up a way to monitor both your implementation and the outcomes you’ve settled on. Who is going to do what?

Systems: Careful attention is needed to identify new systems to support whole-person care. Most aspects of the practice will need to be changed in some way, including front-office, billing, and clinical care workflows. Having a Plan B on the shelf will be useful.

Structure: Determine how the roll-out will occur. It may be best to start a pilot project with a single team, carefully chosen for their ability to embrace change. Their success must be carefully monitored so that processes can change when barriers are discovered.

Style: Decide on whether the change to whole-person care will be incremental or dramatic. Decide on who will lead the implementation and how they will approach it. Develop a means of getting staff members excited. Decide how much input the staff will have in the implementation. Set up a rapid cycle quality improvement plan.

Staff: You will need to enlist key people to make your implementations happen and to make it stick. These may be people in key roles, but you will need to identify an opinion leader and a first follower (the first person in the organization to support the opinion leader) for the implementation to be widely adopted.

Skills: Whole-person care requires a new set of skills and new practices. Identify who will need to receive new training and determine how to provide the training.

The McKinsey model is probably well known to most hospital administrators but less known to clinicians and managers. Soon a five-part continuing medical education series for clinicians, staff and managers will be available that explains the HOPE note and introduces integrative health to the team and managing and monitoring the implementation process.

- Chronic Disease in America. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/tools/infographics.htm. Accessed 10/25/21.

- Why Centering? Centering Healthcare Institute. https://centeringhealthcare.org/why-centering. Accessed 9/23/21.

- Jonas, W, Rosenbaum E. The Case for Whole-Person Integrative Care. Medicina. 30 June 2021. https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/57/7/677/htm. Accessed 11/8/21.

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Zeliadt S, Mohr H. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation – A Progress Report on Outcomes of the WHS Pilot at 18 Flagship Sites. February 18, 2020. Veterans Health Administration, Center for Evaluating Patient-Centered Care in VA (EPCC-VA). https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC_WHSevaluation_FinalReport_508.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Crocker R, Hurwitz JT, Grizzle AJ, et al. Real-World Evidence from the Integrative Medicine Primary Care Trial (IMPACT): Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes at Baseline and 12-Month Follow-Up. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2019, Article ID 8595409. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8595409. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. AcadMed. 2011 Mar;86(3):359-64. doi: 10.1097/ ACM.0b013e3182086fe1. PMID: 21248604. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2011/03000/Physicians__Empathy_and_Clinical_Outcomes_for.26.aspx. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009 Aug;47(8):826-34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. PMID: 19584762; PMCID: PMC2728700. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19584762/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Budzowski AR, Parkinson MD, Silfee VJ. An Evaluation of Lifestyle Health Coaching Programs Using Trained Health Coaches and Evidence-Based Curricula at 6 Months Over 6 Years. Am J Health Promot. 2019 Jul;33(6):912-915. doi: 10.1177/0890117118824252. Epub 2019 Jan 22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30669850/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, at al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:e34. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800389. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1800389. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive Lifestyle Changes for Reversal of Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA, December 16, 1998—Vol 280, No. 23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9863851/. Abstract accessed 7/15/21.

- Thomas KS, Akobundu U, Dosa D. More Than A Meal? A Randomized Control Trial Comparing the Effects of Home-Delivered Meals Programs on Participants’ Feelings of Loneliness. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016 Nov;71(6):1049-1058. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv111. Epub 2015 Nov 26. PMID: 26613620. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26613620/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Huston P, McFarlane B. Health benefits of tai chi: What is the evidence? Can Fam Physician. 2016 Nov;62(11):881-890. PMID: 28661865. https://www.cfp.ca/content/62/11/881. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. Evidence Map of Acupuncture. 2014. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/acupuncture.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. Evidence Map of Mindfulness. 2014. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/cam_mindfulness-REPORT.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Press Ganey. Protecting Market Share in the Era of Reform: Understanding Patient Loyalty in the Medical Practice Segment. White Paper. 2013. http://img.en25.com/Web/PressGaneyAssociatesInc/PerfInsights_PatientLoyalty_Nov2013.pdf?elq=a66e16008286435885d97352358aefd3. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Crocker, R.L., Grizzle, A.J., Hurwitz, J.T. et al. Integrative medicine primary care: assessing the practice model through patients’ experiences. BMC Complement Altern Med 17, 490 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1996-5. Accessed 3/10/21.

- The Impact of Relationship-Based Care. South Central Foundation Nuka System of Care. https://scfnuka.com/impact-relationship-based-care/. Accessed 3/10/21.

- Myklebust M, Pradhan EK, Gorenflo D. An integrative medicine patient care model and evaluation of its outcomes: the University of Michigan experience. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Sep;14(7):821-6. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0154. PMID:18721082. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/63379/acm.2008.0154.pdf;sequence=1 . Accessed 7/15/21.

- Cover Commission. Creating Options for Veterans’ Expedited Recovery: Final Report. January 24, 2020. https://www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.PDF. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Sarnat RL, Winterstein J. Clinical and cost outcomes of an integrative medicine IPA. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2004 Jun;27(5):336-347. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2004.04.007. https://cdn.ymaws.com/nebraskachiropractic.org/resource/resmgr/Docs/Clinical_and_Cost_Outcomes.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Pruitt Z, Emechebe N, Quast T, Taylor P, Bryant K. Expenditure Reductions Associated with a Social Service Referral Program. Popul Health Manag. 2018 Dec;21(6):469-476. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0199. Epub 2018 Apr 17. PMID: 29664702; PMCID: PMC6276598. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29664702/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Jonk Y, Lawson K, O’Connor H, Riise KS, Eisenberg D, Dowd B, Kreitzer MJ. How effective is health coaching in reducing health services expenditures? Med Care. 2015 Feb;53(2):133-40. doi: 10.1097/ MLR.0000000000000287. PMID: 25588134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25588134/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Cherkin DC, Herman PM. Cognitive and Mind-Body Therapies for Chronic Low Back Pain and Neck Pain: Effectiveness and Value. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):556–557. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0113. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/articleabstract/2673371. Accessed 7/15/21.

- De Marchis E, Knox M, Hessler D, Willard-Grace R, Olayiwola JN, Peterson LE, Grumbach K, Gottlieb LM. Physician Burnout and Higher Clinic Capacity to Address Patients’ Social Needs. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019 Jan-Feb;32(1):69-78. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.01.180104. PMID: 30610144. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30610144/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Burn Res. 2017 Sep;6:18-29. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2017.06.003. PMID: 28868237; PMCID: PMC5534210. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28868237/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Eby D, Ross L. Internationally Heralded Approaches to Population Health Driven by Alaska Native/American Indian/Native American Communities. Institute for Healthcare Improvement 8th annual National Forum, 2016. http://app.ihi.org/FacultyDocuments/Events/Event-2760/Presentation-14234/Document-11589/Presentation_L2_Internationally_Heralded_Approaches_to_Population_Health_driven_by_Alaska_NativeAmerican_IndianNative_American_Communities_Eby.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Finnegan J. Integrative medicine physicians say quality of life is better. Fierce Healthcare. August 22, 2017. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/practices/doctorspracticing-integrative-medicine-say-quality-life-better.Accessed 7/15/21.

Topics: Complementary Medicine | Integrative Health