Placebo Guide

LETTER FROM WAYNE JONAS, MD

Modern medicine, which is so powerful in treating acute disease, is missing nearly 80 percent of what contributes to healing for patients with complex, multi-factorial, chronic disease. 1 Drugs do not heal these patients. The inherent healing capacity in each of us will produce most of their healing. But how do we better help patients tap into that healing capacity?

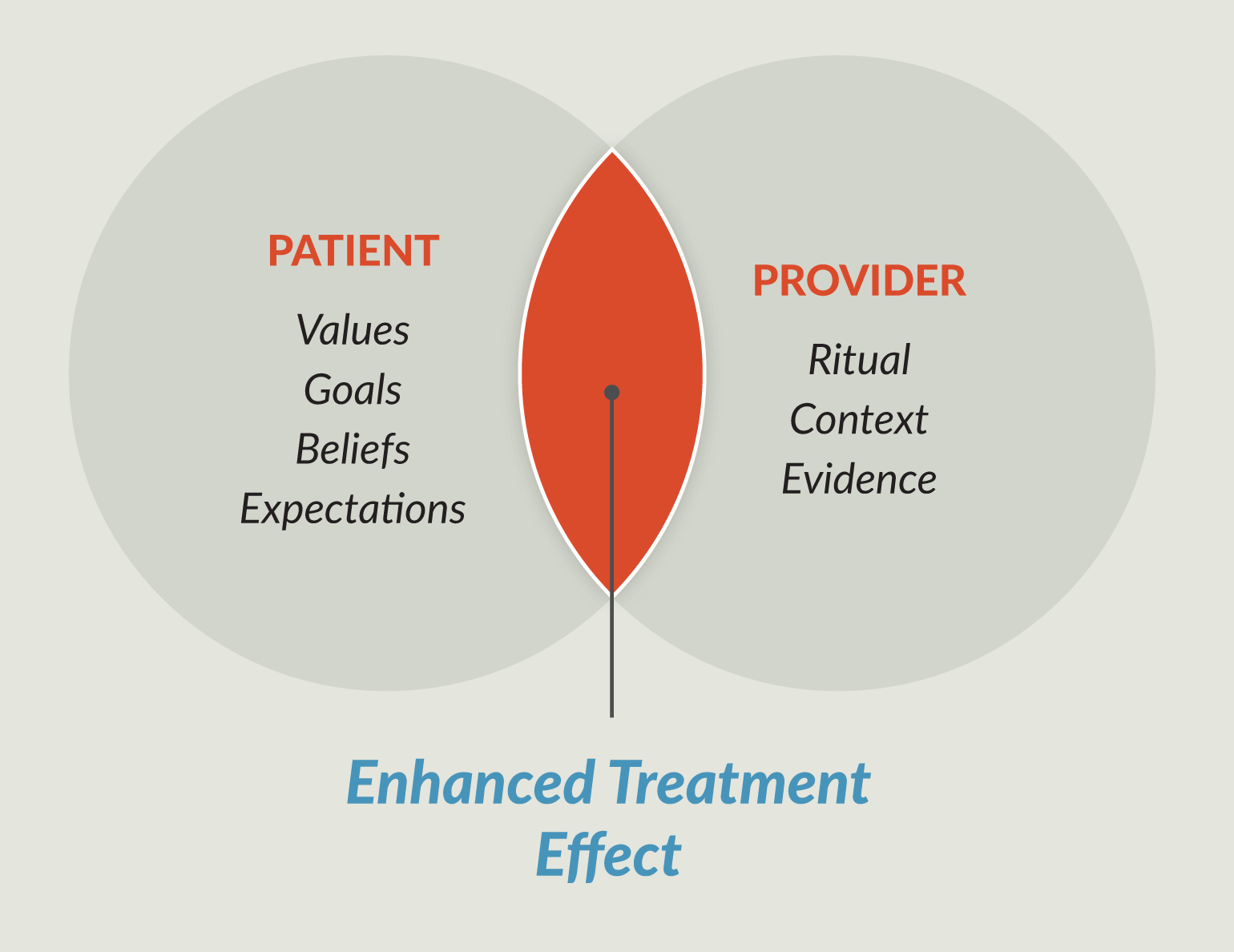

Within a clinical encounter, the ritual and context of a treatment enhance healing. These underlying processes impact us independent of the theory or content of a treatment itself, as shown by the placebo research literature. Ritual and context give the treatment meaning, resulting in measurable physiological and psychological changes that enhance healing. I call this the meaning response. Expectation, especially unconscious expectation, also contributes to the meaning response.

Through the evidence and ethical use of research on the placebo response, you can help your patients tap into their inherent healing capacity. This guide shows you how to integrate knowledge about the placebo response—which is better defined as a response to the context and meaning of a treatment instead of as an inert agent—into your practice.

Many of the 17 evidence-based ways to use the meaning response in your practice

highlighted in this guide are easy to use and don’t require extra time. This guide also offers a practical, systematic process for using this knowledge in your practice.

You can use research on placebo responses to enhance the healing response to any treatment. I hope that you find this guide a useful roadmap to harnessing the power of placebo in your practice.

ENHANCE THE MEANING RESPONSE IN YOUR PRACTICE

THE MEANING RESPONSE

An inert treatment cannot cause a biological response. Thus, a “response” to a placebo alone, as the term is most commonly used, is impossible. The so-called placebo response is actually a response—with measurable biological and psychological changes—to the meaning of a treatment as delivered through treatment rituals. This is the meaning response.

How Placebo Works

Research on the placebo effect has identified three underlying mechanisms of the

meaning response. They are:

- Expectations: Unconscious expectations are especially powerful in the

meaning response. - Rituals: The rituals and context of medicine induce healing or can impair it.

- Conditioning: Repeated exposure to an experience, behavior or event reinforces expectations and rituals, enhancing the response.

When applied in medicine, the meaning response becomes the healing response. Providers can enhance healing from any therapy, whether active or inert, or conventional or complementary, and whether proven or not, using knowledge about the meaning response based on placebo research. This is especially powerful in stimulating the inherent healing capacity of patients with complex, multi-factorial, chronic disease.

THE ETHICAL USE OF KNOWLEDGE FROM PLACEBO RESEARCH

Many physicians consider placebo to be giving patients an inert pill without telling them it is inert—and so is deceiving patients. Being deceptive would make the use of placebo unethical. However, using an inert pill (a placebo pill) or describing placebo as inert is neither required nor recommended to access the healing power of meaning.

“What is unethical is if physicians do not use the power of the so-called placebo response in the best interest of patients.”

The use of research-based knowledge on placebo to achieve the meaning response should not be deceptive. The ritual of the clinical encounter and an explanation about how the treatment works in the context of a trusting physician–patient relationship is a powerful clinical tool—and an ethical way to use the power of the

placebo response.

Most ways to harness the power of placebo to enhance healing involve the skill in the clinical encounter and the physician’s manner and behavior. Many are easy to do and don’t take extra time.

7 Easy Ways to Harness the Power of Placebo Every Day 2

- Inform the patient about what he/she/they can expect and use positive messages. 3 4 5 Patients who are better informed about their treatment and who receive positive messages about what to expect heal more. Let the patient know the intention of the treatment effects.

- Listen and provide empathy and understanding. 5 6 Listen to the patient and respond in a way that enhances the therapeutic effect through positive messages based on the patient’s expectations. When possible, touch the patient with empathy and reassurance.

- Be warm and caring when delivering treatment. 5 Use a calm tone of voice, look at the patient and touch him/her/them.

- Be confident and credible when delivering treatment. 7 8 9 Present the treatment in a way that shows your confidence in its power to heal. Understand the treatment’s mechanism of action, ensure that credible science supports it and explain how it works to the patient.

- Incorporate reassurance, relaxation, suggestion and anxiety-reduction methods. 10 11 12 For example, a smile, a touch or an expression of caring can provide reassurance and induce relaxation. Frame the goals of treatment in positive language (how much improvement the patient can expect) rather than negative language (chance of not working).

- Deliver a safe and easy-to-use conditioned stimulus along with the therapy. 13-20 The repeated ritual of treatment (taking a pill each day), preparing special food and linking treatment to smell or light exposure are examples.

- Align all beliefs congruently. 8 21-23 Align your beliefs with those of the patient, his/her family, and the culture.

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE POWER OF MEANINGFUL MESSAGES

Many studies illustrate the role of the physician’s manner and behavior in providing

meaningful messages that enhance the healing response.

Healing by offering positive messages

In one study, for example, 200 patients with symptoms but no abnormal physical disease were randomized to a positive or a negative consultation. Two weeks later, the percentage of patients who said they were better was: 5

- 39% for patients who had negative consultations

- 64% for patients who had positive consultations

“In my own practice, I saw that a patient’s response to my treatments was often significantly affected by how I delivered them.

Sometimes even subtle inflections in my voice—or the expression in my eyes—while delivering the diagnosis and therapy could launch a patient either on a path toward healing or a spiral of despair and a worsening of the condition.”

Healing by providing informed consent

In another study, patients with cancer being treated for pain were randomized to either receive or not receive informed consent. They were further randomized to receive placebo or naproxen. Researchers found that: 24

- Patients who received informed consent reported more pain relief—whether they were taking naproxen or placebo—than patients who did not receive informed consent.

Healing by understanding patients’ expectations

Studies in Parkinson disease illustrate the role of expectation in a healing response. In one study, 10 patients with Parkinson disease treated with deep brain stimulation thought their conditions improved when they thought the device had been turned “on” when it was actually “off.” 25

In another study, when patients with Parkinson disease expected to receive a medicine that would stimulate their bodies to produce dopamine and reduce their symptoms, but were actually given a placebo, their bodies begin to produce dopamine. 26

10 MORE WAYS TO HARNESS THE POWER OF PLACEBO FOR YOUR PATIENTS

Here are 10 more ways to enhance healing with placebo:

- Follow up. 27 Reinforce the therapeutic interaction by following up with patients through automated reminders such as text messages or phone calls from staff or more frequent office visits. This taps into conditioning, a mechanism of the placebo response, by reinforcing it with the expectancy, another mechanism of the placebo response, to enhance the healing response started during the office visit.

- Determine which treatments your patient believes in. 8 16 28 Talk to the patient about his/her/their beliefs about treatments and recommend safe treatments that are aligned with those beliefs. Make sure you believe in them too.

- Use a light, laser or an electronic device to deliver and track the treatment, when possible. 29 Patients often believe that these devices help them heal. This may produce a conditioning response. Be sure the light, laser or electronic device is safe and not expensive. Make sure to explain why you are using it so you don’t deceive the patient.

- Match the appearance to the desired effect. 30 31 The color and size of pills make a difference. For example, anti-anxiety, sedative and anti-depression medications are usually in soft colors such as blue, purple or pink, while stimulants are usually bright colors such as orange, yellow or red.

- Use more frequent dosing. 31 Taking a pill or any action that reinforces a therapeutic expectation can enhance an associated healing response. However, patients don’t always want to take pills more frequently. Find the right balance; don’t just reflexively reduce the frequency.

- Apply therapies in “therapeutic” settings. 32 Clinics and hospitals are more powerful therapeutic settings than the patient’s home.

- Pay attention to the route of administration. 33 Needles, when appropriate, produce a greater effect than pills.

Looks Matter

How pills or a container of pills looks makes a difference for the effectiveness of the medicine inside. A randomized, controlled trial compared four ways to treat headache in 835 women:

- Aspirin with a well-known brand name label

- The same aspirin with no label

- Placebo labeled as the well-known brand of aspirin

- Placebo with no label

Researchers found: 33

- Taking a pill (whether placebo or aspirin) improved the headache at about a two-to-one ratio over no treatment

- Among the patients taking placebo, headache relief was reported one hour after taking the pill in:

» 64% of women who took the branded placebo

» 45% of the women who took the unbranded placebo

- Use the newest and most prominent treatment available. 29 34 Patients often believe that new treatments work best. However, new treatments are usually expensive, so find the balance that works for each patient.

- Use a well-known name brand identified with success. 35 Patients often believe that well-known brands work best. This method may be difficult to use, however, due to the increased use of generic drugs, which are less expensive.

- Cut or stick the skin or poke into an orifice when this is appropriate and important. 34 This enhances the healing response.

A VAST BODY OF EVIDENCE FOR MEANING IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Along with the studies related to some of the ways to harness the power of placebo, a vast body of evidence supports the general use of meaning responses in clinical practice.

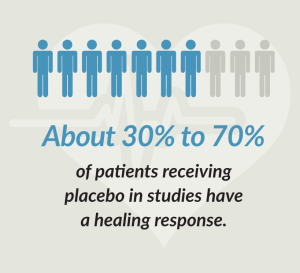

Overall, studies have shown a healing response rate of between 30 and 70 percent for inert treatments:

Overall, studies have shown a healing response rate of between 30 and 70 percent for inert treatments:

- Back in 1955, Henry Beecher, MD, reported that about one-third of all effects are due to placebo in the Journal of the American Medical Association. 36

- Since then, several studies have reported response rates to inert treatments of up to 70% or more. 37

Healing pain

Pain often responds to healing rituals. A large “individual data meta-analysis” combined data from 29 large, high-quality studies of acupuncture for chronic pain involving 17,922 patients. Results showed that: 38

- Approximately 40% of the effect was specific to acupuncture.

- The other 60% of the effect was due to the art of how acupuncture was delivered—the ritual, context and meaning that accompanied its delivery.

Researchers also reported that:

- Patients receiving acupuncture had less pain, with scores 0.23 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13-0.33), 0.16 (95% CI, 0.07-0.25) and 0.15 (95% CI, 0.07-0.24) standard deviations lower than sham controls for back and neck pain, osteoarthritis and chronic headache, respectively. The effect sizes in comparison to no acupuncture controls were even larger: 0.55 (95% CI, 0.51-0.58), 0.57 (95% CI, 0.50-0.64) and 0.42 (95% CI, 0.37-0.46), for back/neck, osteoarthritis and headache, respectively.

A PRACTICAL PROCESS FOR ENHANCING HEALING

Healing other conditions

Other conditions shown to improve during placebo treatments include anxiety and depression, immune and autoimmune diseases, allergic conditions and respiratory problems such as asthma. 39 In depression, for example, studies have shown that anti-depressants and placebo are almost equally effective 40:

- A little over half of people who take anti-depressants get better.

- Almost half of people who take a placebo for depression get better.

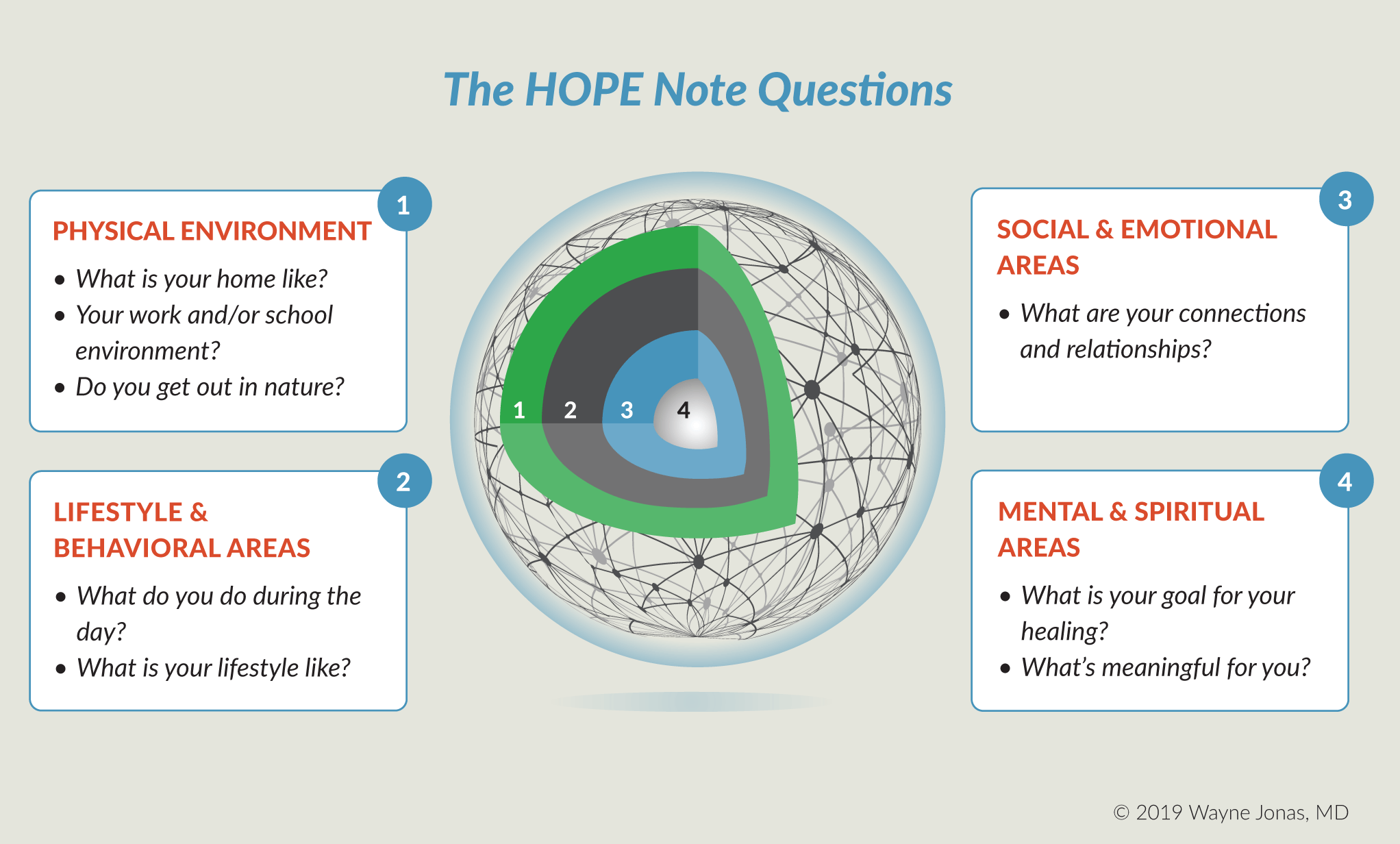

Like other clinical skills, using the mechanisms of placebo to enhance healing requires knowledge and practice. The HOPE (Healing-oriented Practices and Environments) note provides a practical, systematic process for doing this

A THERAPEUTIC RITUAL BASED ON THE MEANING OF TREATMENT

The HOPE note is a therapeutic ritual that guides you through a patient-centered process to identify the patient’s values and goals. It draws heavily from research on the placebo effect to apply the mechanisms of the meaning response.

The meaning response is what really happens in response to placebo treatments. Measurable physiological and psychological changes occur due to the rituals and context of therapy—whether the treatment is active or inert. The rituals and context of therapy create meaning. The “same” treatment can have significantly different effects depending on the physician’s behavior and the care setting. When applied in medicine, the meaning response becomes the healing response.

“Placebos don’t heal. It is the person who heals and the providers who help them through their relationships and the meaning and rituals of the treatment process. This is how you apply placebo research in practice.”

USING THE HOPE NOTE TO ENHANCE THE HEALING RESPONSE

Building off the SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment and plan) note that providers apply every day in practice, the HOPE note is a systematic process for infusing knowledge from placebo research into therapeutic encounters. It reframes the patient experience from one of disease treatment to one that emphasizes self-healing and integrates evidence-based complementary and lifestyle approaches into conventional medical care. The HOPE note is a tool for applying an integrative, or whole person, approach in health care.

Focusing on what matters most to the patient

The HOPE note guides the provider in identifying what matters most to the patient in life and for healing and tailoring the treatment to this purpose. The process begins with finding out what matters to the patient. During the clinical encounter, the provider identifies the patient’s values and goals in life—why the patient wants health. Then the provider discusses the medical care and self-care that the patient is using or has used.

Finally, the provider aligns what matters to the patient with his/her/their beliefs and expectations and uses evidence from placebo research to integrate with those practices. The provider then identifies a therapy that actively engages the patient in their own healing and will enhance the patient’s healing response for achieving their life goals. This person-centered process creates a therapeutic alliance between provider and patient.

The HOPE note discussion and action plan

You begin the HOPE note by asking the patient a series of questions geared to evaluate the areas of life that impact his/her health. You and the patient then develop a patient action plan.

The HOPE note template has specific questions in each area. (Click on the HOPE note questions.)

You and the patient agree upon the plan and set and track goals. Continuing support can come through your team, and/or include a health coach, group visits, health apps and ongoing informational resources.

CHALLENGES OF USING KNOWLEDGE FROM PLACEBO RESEARCH IN YOUR PRACTICE

While the evidence supporting the meaning response is strong, there are several challenges in using knowledge from placebo research in your practice.

Changing the physician’s mindset

Outside of serious conditions or injuries, most healing occurs spontaneously and through the patient’s inherent healing capacity. Going into these encounters with this knowledge helps.

The therapeutic interaction between physician and patient enhances this natural recovery process. Placebo research offers many effective ways to enhance this healing. Pay attention to this often “hidden” interaction throughout your day.

Being aware of the physician’s impact

The physician’s manner and behavior have strong psychological and physiological effects on patients. The mind and body are not separate. You must be aware of this and not underestimate the impact of behaviors that might seem subtle or trivial to you. Once you are aware of this, customize what you say and do to enhance the healing response during clinical encounters with patients.

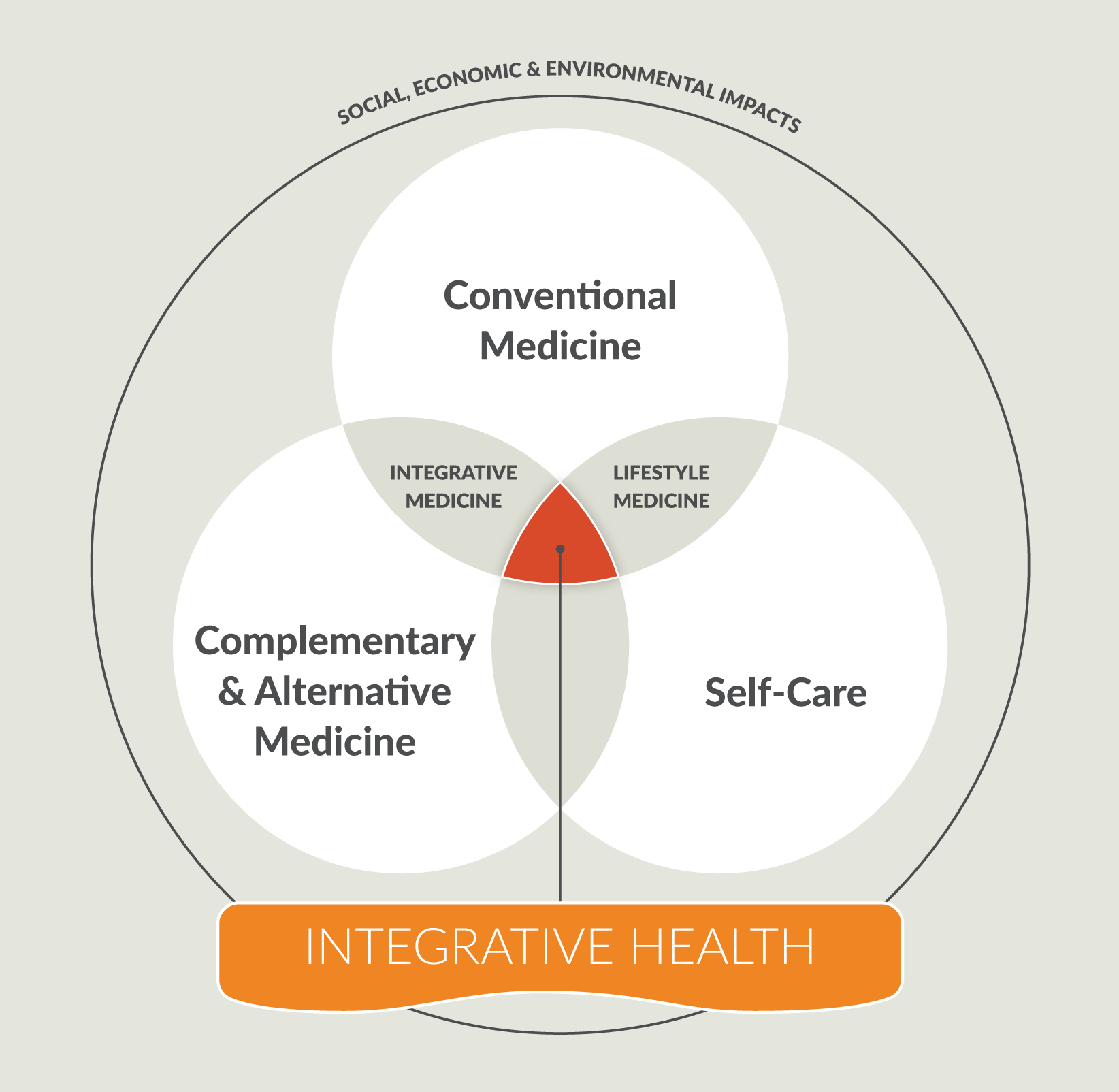

INTEGRATIVE HEALTH AND KNOWLEDGE FROM PLACEBO RESEARCH

Integrative health is the pursuit of personal health and wellbeing foremost, while addressing disease as needed with the support of a health care team dedicated to all proven approaches—conventional, complementary and self-care.

Optimal health and wellbeing arise when we attend to all factors that influence healing, including:

- Medical treatment

- Personal behaviors

- Social and emotional dimensions

- Mental and spiritual factors

- Social, economic and environmental determinants of health

Integrative medicine is the coordinated delivery of evidence-based conventional medical care, complementary medicine and drugless approaches for producing optimal health and wellbeing.

Integrative primary care is the coordinated delivery of evidence-based conventional medical care, complementary medicine and lifestyle medicine within a primary care practice.

Lifestyle medicine incorporates evidence-based self-care and behavioral (lifestyle) approaches into conventional medical practice to enhance health and healing.

Integrative health redefines the relationship between the practitioner and patient by focusing on the whole person and the whole community. It is informed by scientific evidence and makes use of all appropriate preventive, therapeutic, and palliative approaches; health care professionals and disciplines to promote optimal health and wellbeing. This includes the coordination of conventional medicine, complementary/alternative medicine and lifestyle/self-care.

The meaning response involves the use of information from research on the placebo effect to enhance healing from any treatment—whether active or inert, conventional or complementary. Methods to bring integrative care into primary care such as the HOPE note draw heavily from placebo research.

CONCLUSION

Benefits of Using Information From Research on Placebo in Your Practice

- Durable low-risk, healing response

- More effective than treatments the patient doesn’t believe in

- A safe choice when patients can’t tolerate a treatment

- A cost-effective choice when patients can’t afford a treatment

- Less physician burnout by putting relationships back into health care

CONCLUSION

The true role of the mechanisms underlying the placebo response in enhancing healing is overshadowed by the traditional meaning of placebo as an inert substance and the myth of its ability to produce a response. By reframing placebo as a response to the context and meaning of a treatment, you can tap into the inherent healing capacity of your patients and enhance the effects of any treatment.

“Information from research on placebo enhances the effectiveness of any treatment.”

The 17 ways to harness the power of research on placebo in this guide are especially useful in treating patients with chronic disease. Most of these

ways focus on the physician–patient encounter and the rituals of treatment.

Many are easy to integrate into your daily practice of medicine.

RESOURCES

Jonas WB. The myth of the placebo response. Front Psychiatry. August 16, 2019.

(Accessed January 9, 2020).

Jonas WB. Reframing placebo in research and practice. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1572):1896-1904. (Accessed January 9, 2020).

Walach H, Jonas WB. Placebo research: the evidence base for harnessing self-healing capacities. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(suppl 1):S103-S112. (Accessed January 9, 2020).

Moerman DE, Jonas WB. Deconstructing the placebo effect and finding the meaning response. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(6):471-476. (Accessed January 9, 2020).

Jonas, WB. How Healing Works. Ten Speed Press. 2018

THE HOPE NOTE

The HOPE Note Guide (Long) (PDF)

The HOPE Note Overview (Short) (PDF)

HOPE Note questions

REFERENCES

- DrWayneJonas.com. Integrative Health Balances Healing and Curing. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Walach H, Jonas WB. Placebo research: the evidence base for harnessing self-healing capacities. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(suppl 1):S103-S112. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Bergmann J-F, Chassany O, Gandiol J, et al. A randomised clinical trial of the effect of informed consent on the analgesic activity of placebo and naproxen in cancer patients. Clin Trials Metaanal. 1994;29:41-47. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Skovlund E. Should we tell trials patients that they might receive placebo? Lancet. 1991;337:1041. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Thomas KB. General practice consultations: Is there any point in being positive? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;294:1200-1202. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Brody H. The placebo response. Recent research and implications for family medicine. J Family Pract. 2000;49:649-654. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Uhlenhuth EH, Richels K, Fisher S, Park LC, Lipman RS, Mock J. Drug, doctor’s verbal attitude and clinical setting in the symptomatic response to pharmacotherapy. Psychopharmacologia. 1966;9:392-418. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Cassidy CM. Chinese medicine users in the United States. Part II: preferred aspects of care. J Altern Complement Med. 1998;4:189-202. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Gracely RH, Dubner R, Deeter WR, Wolskee PJ. Clinicians expectation influence placebo analgesia [letter]. Lancet. 1985;i:43.

- Vase L, Robinson ME, Verne GN, Price DD. The contributions of suggestion, desire, and expectation to placebo effects in irritable bowel syndrome patients: an empirical investigation. Pain. 2003;105:17-25. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Gheorghiu VA, Netter P, Eysenck HJ, Rosenthal R, eds. Suggestion and Suggestibility: Theory and Research. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1989. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Stefano GB, Fricchione GL, Slingsby BT, Benson H. The placebo effect and relaxation response: neural processes and their coupling to constitutive nitric oxide. Brain Res Rev. 2001;35:1-19. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Ader R. Behavioral conditioning and immunity. In: Fabris N, Garaci E, Hadden J, Mitchison NA, eds. Immunoregulation. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1983:283-313.

- Ader R, Cohen N. Behaviorally conditioned immunosuppression. Psychosomat Med. 1975;37(4):333-340. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Wickramasekera I. A conditioned response model of the placebo effect: Predictions from the model. In: White L, Tursky B, Schwartz GE, eds. Placebo: Theory, Research, Mechanisms. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1985:255-287. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Kirsch I. Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior. Am Psychol. 1985;40:1189-1202. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Voudouris NJ, Peck CL, Coleman G. The role of conditioning and verbal expectancy in the placebo response. Pain. 1990;43(1):121-128. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Voudouris NJ, Peck CL, Coleman G. Conditioned response models of placebo phenomena: further support. Pain. 1989;38(1):109-116. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Voudouris NJ, Peck CL, Coleman G. Conditioned placebo responses. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48(1):47-53. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Montgomery GH, Kirsch I. Classical conditioning and the placebo effect. Pain. 1997;72(1-2):107-113. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Uexküll TV. Biosemiotic research and not further molecular analysis is necessary to describe pathways between cells, personalities, and social systems. Adv J Mind–Body Health. 1995;11:24-27.

- Moerman DE. Cultural variations in the placebo effect: ulcers, anxiety, and blood pressure. Med Anthropol Q. 2000;14(1):51–72. Accessed January 10, 2020

- Phillips DP, Ruth TE, Wagner LM. Psychology and survival. Lancet. 1993;342:1142-1145. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Bergmann JF, Chassany O, Gandiol J, et al. A randomised clinical trial of the effect of informed consent on the analgesic activity of placebo and naproxen in cancer pain. Clin Trials Metaanal. 1994;29(1):41-47. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Mercado R, Constantoyannis C, Mandat T, et al. Expectation and the placebo effect in Parkinson’s disease patients with subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. Sep 2006;21(9):1457-1461.

- de la Fuente-Fernandez R, Ruth TJ, Sossi V, Schulzer M, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ. Expectation and dopamine release: mechanism of the placebo effect in Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2001;293(5532):1164-1166. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Stewart-Williams S, Podd J. The placebo effect: dissolving the expectancy versus conditioning debate. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(2): 324–340. Accessed January 27, 2020.

- Frank JD. Persuasion and Healing: A Comparative Study of Psychotherapy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1961.

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Transmyocardial laser revascularization. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1075-1076.

- de Craen AJM, Moerman DE, Heisterkamp SH, Tytgat GNJ, Tijssen J, Kleijnen J. Placebo effect in the treatment of duodenal ulcer. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:853-860. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- de Craen AJ, Roos PJ, Leonard de Vries A, Kleijnen J. Effect of colour of drugs: Systematic review of perceived effect of drugs and of their effectiveness. BMJ. 1996;313:1624-1626. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- de Craen AJ, Tijssen JG, de Gans J, Kleijnen J. Placebo effect in the acute treatment of migraine: subcutaneous placebos are better than oral placebos. J Neurol. 2000;247(3):183-188. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Branthwaite A, Cooper P. Analgesic effects of branding in treatment of headaches. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1576-1578. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Johnson AG. Surgery as a placebo. Lancet. 1994;344:1140-1142.

- Margo CE. The placebo effect. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;44(1):31-44.

- Beecher HK. The powerful placebo. JAMA. 1955;159(17):1602-1606. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Roberts AH, Kewman DG, Mercier L, Hovell M. The power of nonspecific effects in healing: implications for psychosocial and biological treatments. Clin Psychol Rev. 1993;13(5):357-391. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1444-1453. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- DrWayneJonas.com. The Placebo Response: How Cultural Context Influences Healing. Samueli Institute. 2015. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Kirsch I. The Emperor’s New Drugs, Exploding the Antidepressant Myth. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2010. Accessed January 12, 2020

ABOUT THE AUTHOR – DR. WAYNE JONAS

Dr. Jonas is a practicing family physician, an expert in integrative health and whole person care delivery, and a widely published scientific investigator. Dr. Jonas is the president of Healing Works Foundation. Additionally, Dr. Jonas is a retired lieutenant colonel in the Medical Corps of the United States Army.

Dr. Jonas was the director of the Office of Alternative Medicine at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) from 1995-1999, and prior to that served as the Director of the Medical Research Fellowship at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

His research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals such as the Journal of the American Medical Association, Nature Medicine, Journal of Family Practice, Annals of Internal Medicine, and The Lancet. Dr. Jonas received the 2015 Pioneer Award from the Integrative Healthcare Symposium, the 2007 America’s Top Family Doctors Award, the 2003 Pioneer Award from the American Holistic Medical Association, the 2002 Physician Recognition Award of the American Medical Association, and the 2002 Meritorious Activity Prize from the International Society of Life Information Science in Chiba, Japan.

Topics: Behavior & Lifestyle | Chronic Disease | Complementary Medicine | Integrative Health