Women and Pain: Taking Control and Finding Relief

Pain

If you have chronic pain, you’re not alone. An estimated 25.3 million adults in the United States report severe, daily pain, significantly more women than men, while 55 percent of U.S. adults report at least some pain in the past three months. Chronic pain is one of the most frequent reasons for physician visits and among the most common reasons for taking medication.

But there’s a gender gap when it comes to pain. Women have more frequent, longer lasting, and severe pain than men. For instance, one national survey found that while about 16 percent of white men and 8 percent of black men reported severe pain, those numbers jumped to about 22 percent for white women and 11 percent for black women, respectively.

Women are also more likely to develop painful diseases, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, vulvodynia, and temporomandibular disorders (TMJ) than men. They also report greater pain severity than men from certain conditions, such as cancer. And women simply pay attention to pain from physical conditions more than men. They recognize when something is wrong. Men, on the other hand, have a tendency to ignore pain when they should pay attention to it.

Women also differ in their response to pain medications. They tend to need higher amounts of pain medications immediately after surgery, while men tend to use more pain relievers later in the recovery period. Conversely, some medications (the partial kappa-opioid agonists, such as nalbuphine [Nubain] and pentazocine [Talwin]), can provide greater pain relief in women than men, although opioids such as morphine and codeine can lead to more nausea and vomiting in women than men.

The question that has plagued researchers for decades is: “Why?”

Part of it could be anatomy. Women have more nerve receptors than men, so they may be hard-wired to feel more pain. Even something as seemingly minor as the thickness of your skin or the size of your body can affect pain perception. Another reason may be that women are more likely to see a doctor than men, so maybe they’re just getting diagnosed more often.

Genetics also plays a role, affecting how long neurons that transmit pain signals to the brain survive, the strength of pain response, and pain tolerance, perception, and response to pain relievers.

But we also know that reproductive hormones—estrogen and progesterone in women, testosterone in men—play a role in these pain-related gender differences.

In women, the continual variation in hormone levels through puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and the menopause transition contribute to these sex differences. For instance, before puberty, there are no significant differences in the development of painful conditions between boys and girls. Afterward, the differences are dramatic, with women two to six times more likely to develop chronic pain conditions such as headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia. There are also differences in pain levels and frequency after menopause.

Pain intensity tends to increase when estrogen levels are low and progesterone levels are high, as they are during the second half of the menstrual cycle. This may be because there are more naturally occurring “feel good” chemicals in the brain when estrogen levels are high.

You can imagine the natural benefit to this: estrogen levels are highest during pregnancy and childbirth, thus providing some natural pain relief. Studies show that during pregnancy, when estrogen levels are high and steady, many pain conditions improve and pain sensitivity is lower. There’s even a name for it: pregnancy-induced analgesia. One study found that women with TMJ reported less pain as pregnancy progressed (and estrogen levels rose) and had more pain after surgical menopause (when estrogen levels plummet).

Finally, reproductive hormones can also influence how well opioids and other pain relievers work.

Women and Cancer Pain

Women with cancer face unique challenges when it comes to pain management. They report greater pain severity than men from cancer conditions, and this disparity needs to be addressed in their treatment plans. At least 20 to 50 percent of people with cancer report having pain, making it one of the most common side effects of both the disease and its treatment.

Cancer pain can have several sources:

- Direct injury to nerves from the cancer itself

- Cancer spreading to bones or other structures in the body

- Inflammation from the disease or treatments

- Side effects from cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy

While medications—particularly opioids—are commonly prescribed for cancer pain, it’s important to know that they aren’t your only option. Many women benefit from a whole health approach that combines traditional pain management with complementary therapies. Some effective non-medication approaches include:

- Massage therapy

- Guided imagery and meditation

- Breathwork techniques

- Music therapy

- Exercise (when appropriate and approved by your healthcare team)

- Acupuncture

If you’re concerned about using opioids for cancer pain, discuss this with your healthcare team. While the risk of addiction is often lower when opioids are used appropriately for cancer pain, your doctors should know about any personal or family history of substance use disorders to help create the safest pain management plan for you.

Taking Control of Your Cancer Pain

One way to help manage pain is to keep a diary of your symptoms. You can track:

- Pain levels through the day

- What makes pain better or worse

- How different treatments affect your pain

- How it affects your daily activities and quality of life

Working with a health care provider called a palliative care specialist is another option. He or she can help you manage symptoms, including pain, at any time during cancer and treatment, including after treatment ends. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care, although they can be confused because people on hospice often use palliative care.

When managing cancer pain, communicate openly with your healthcare team about:

- Your pain levels and how they affect your daily life

- Any concerns about pain medications

- Interest in complementary therapies, such as massage or cannabis products

- Exercise and physical activity

- How the pain affects you emotionally

Remember that almost all cancer pain can be controlled through proper management. Don’t hesitate to speak up and get second opinions if you feel your pain isn’t being adequately treated. The goal is to find the combination of treatments—both medical and complementary—that works best for you while maintaining the highest possible quality of life during your cancer journey.

Life Experiences and Emotional Status

A woman’s past experiences, particularly those involving trauma and abuse, as well as her current emotional state and life stresses, have an enormous impact on her level of pain and even the development of painful conditions. Your history may increase your body’s response to pain or make you more susceptible.

One study of 380 women found that those who reported they had been victims of bullying or abuse were more likely to experience painful genital or urinary conditions. What happens is that their body remains on high alert. In most people, the normal response to pain is that the body adjusts and the pain diminishes. But in people with a history of trauma, the body exists in constant “alert” mode, leading to a hyperawareness of external and internal stressors.

Even socioeconomic status and work environment can impact the perception of pain.

This is why it is so important that you work with your health care team to identify issues beyond the physical—including the emotional, social, mental, and spiritual—to help you.

Woman and Opiods

Oxycodone and the Ongoing Opioid Crisis

Oxycodone, a semi-synthetic opioid, continues to play a significant role in the opioid epidemic, though its impact has evolved over time. First marketed as a long-acting pain reliever under the brand name OxyContin, it became widely abused due to its ability to deliver a euphoric high when crushed or dissolved. In 2010, the manufacturer introduced an abuse-deterrent formulation to curb misuse. However, this reformulation had unintended consequences, as many people transitioned from prescription opioids to illicit substances like heroin and fentanyl, increasing overdose rates.

The Shift from Prescription Opioids to Illicit Drugs

Recent data indicate that while prescription opioid misuse remains a problem, the majority of opioid overdose deaths now involve illicit drugs such as fentanyl and heroin. A study projected that by 2025, nearly 80% of opioid overdose deaths will result from these illicit substances. This shift reflects a broader trend where fewer individuals are initiating opioid misuse with prescription medications and instead are starting directly with illicit opioids like fentanyl.

Gender-Specific Impacts

Women have been disproportionately affected by prescription opioid misuse in certain ways. Fatal opioid overdoses are three times higher than a decade ago. For the 12 months ending in December 2021, there were nearly 80,000 deaths from opioid overdoses, the highest in the U.S. to date. Prescription opioid pain relievers accounted for the overwhelming majority of opioids misused in 2020 (more than 90%). Women are more likely than men to be prescribed opioid analgesics for the treatment of pain, sometimes using them with benzodiazepines such as Valium. Women are also more likely to say that they use opioids to help with stress or depression, to crave the opioids more, and in one study, to have more medical problems than the men who participated.

These factors are likely to be part of why women tend to start misusing opioids more quickly than men and are more likely to develop opioid use disorder. This is especially concerning when we learn that rates of fatal opioid-involved overdoses since 1999 have increased faster in women than men (14-fold vs. 10-fold). Despite these differences, treatment approaches often remain gender-neutral, which may limit their effectiveness for women.

Biological Factors in Oxycodone Misuse

Emerging research highlights the role of sex hormones in influencing opioid use behaviors. For example,

studies using animal models suggest that hormonal fluctuations in females may reduce the reinforcing

effects of oxycodone during certain phases of the estrous cycle. This underscores the importance of

considering biological differences in developing strategies to combat opioid use disorder.

Health Risks and Overdose Effects

Chronic use of oxycodone can lead to severe health consequences, including respiratory depression, liver damage (when combined with acetaminophen), and addiction. Overdose symptoms include extreme drowsiness, slowed breathing, pinpoint pupils, and potential death. These risks increase when you consider the increasing presence of fentanyl in pills marketed as oxycodone.

Whole Person Pain Treatment is More Important Than Ever

These disturbing statistics, and a trend of women using, depending on and dying from opioid use, make it even clearer that the health of the whole person — the whole woman — is essential to address. Incorporating a tool such as the HOPE Note into primary care, taking a Personal Health Inventory, and providing support for women who have become dependent on prescription opioids or those bought in the community is essential.

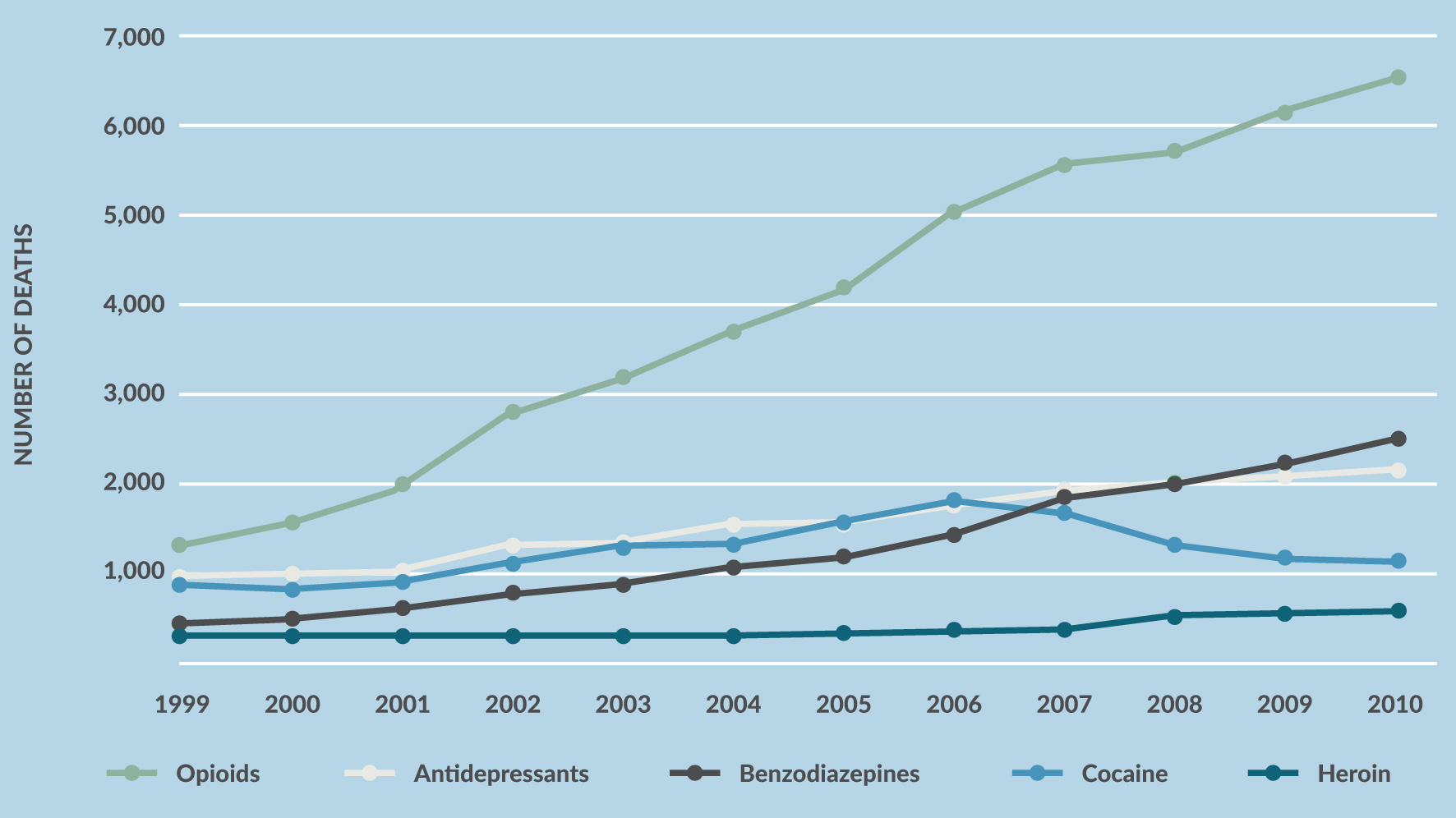

Figure 1. Drug Overdose Deaths Among Women

Source: National Vital Statistics System, 1999–2010 (deaths include suicides)

Drug overdose deaths among women, by select drug class, United States, 2004–2010. Data from National Vital Statistics System.

Quintiles IMS. An Analysis of the Impact of Opioid Overprescribing in America: Pacira Pharmaceuticals; September 2017.

Women are also using more opioids during pregnancy, putting their infants at risk of dependence and post-partum withdrawal. This, in turn, has led to what experts call an epidemic of infants born already dependent on opioids, who then have to go through a painful withdrawal process.

While opioids definitely have a place in the treatment of acute pain (such as after surgery or accidents) and in palliative care (such as during a sickle cell crisis or near the end of life), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other medical organizations recommend starting with non-opioid alternatives as a first-line treatment for chronic pain, including acetaminophen (Tylenol), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (i.e., Motrin, Aleve), antidepressants, and anticonvulsants, and non- drug approaches such as yoga, manipulation, acupuncture, massage, and mind-body methods.

Facing Discrimination

Numerous studies dating back decades attest to the fact that the medical system does not take women’s pain seriously, whether chronic or acute. For instance, a 2011 report from the National Institutes of Health found that medical professionals were more likely to dismiss women’s reports of pain.

An oft-quoted study of 981 men and women seen in the emergency room found that women were 13 to 25 percent less likely to receive strong pain medication, despite the fact that they had the same pain scores as men and waited about 16 minutes longer to get medication. Women with endometriosis, an extremely painful reproductive condition, often go years before getting a diagnosis. They are told their excruciating pain is a normal part of menstruation, or even that it is all in their heads—and are prescribed antidepressants.

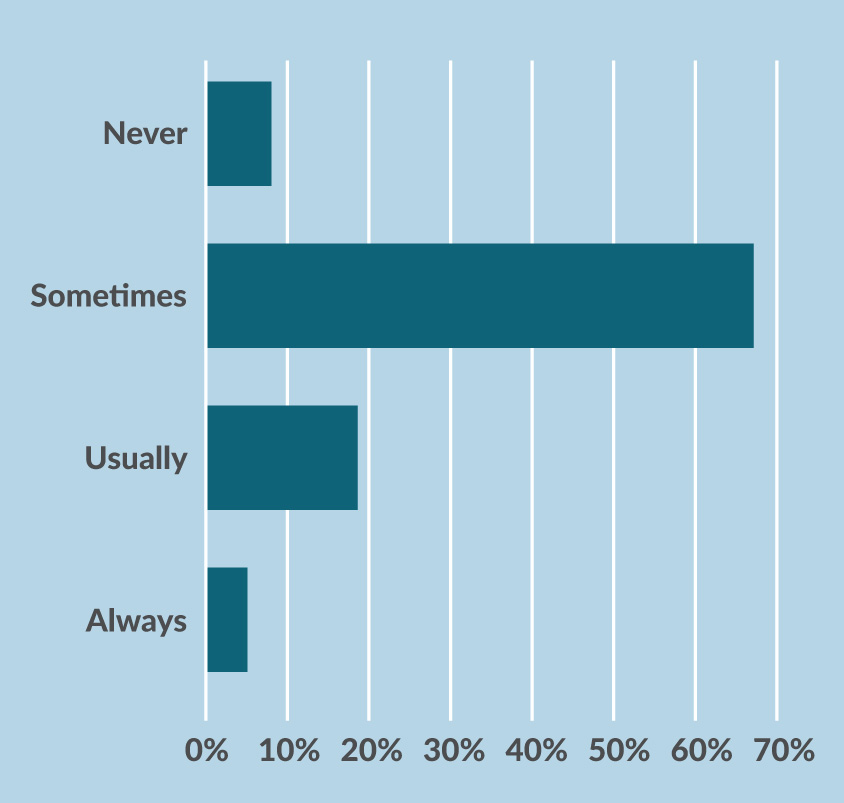

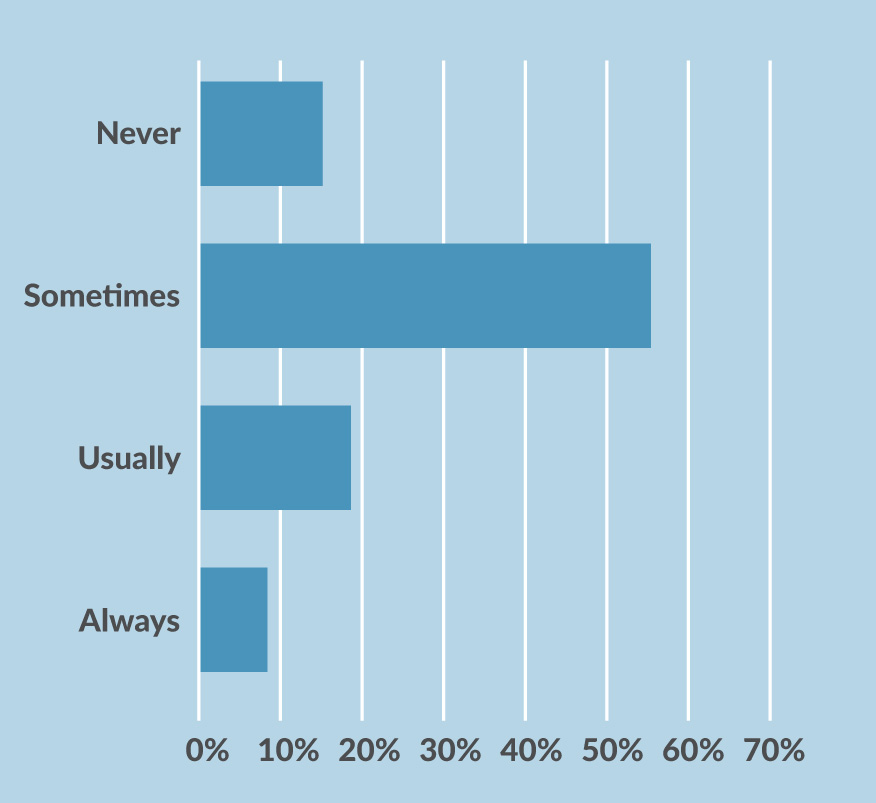

Meanwhile, a 2015 survey of more than 2,400 women with chronic pain, most with fibromyalgia and/or back pain, conducted by National Pain Report and For Grace, a non-profit organization, found that more than 90 percent of those with chronic pain thought the system discriminates against women with pain, with 65 percent saying they thought doctors took their pain less seriously. The survey also found that women believe there is a gender bias in how doctors treat their pain (Figures 2 and 3). Interestingly, it didn’t seem to matter if the doctor was male or female.

Figure 2. Do you feel you are treated differently by doctors because you are a woman?

Figure 3. Do you think the health care system discriminates against female patients?

Source: Women in Pain Survey. 2015.

In addition, 75 percent of the survey respondents said their doctors told them they had to learn to live with the pain. More than half said their doctors didn’t know what was wrong with them, while 52 percent said they were told that since they “looked good,” they must be feeling better. Forty-five percent were told that the pain was all in their head.

This is why it’s so important that you take a proactive role in finding the right doctors and other health care practitioners to work with. You have to advocate for yourself at a time when your energy and drive may be sapped by the pain. If you can’t do this on your own, bring someone with you to appointments and have them help you research providers to find those who will listen to you and provide the evidence-based care you deserve. Ideally, that will be an integrative medicine physician, where I think you’ll find your best chance of being listened to, believed, and treated with respect.

Keep in mind, though, that communication goes both ways. While you should expect your doctor to communicate openly with you, respect your goals and decisions, and take your pain seriously, you also have a role. You must engage in your own self-care for health.

My advice is to keep a pain diary for at least a week before your visit in which you rate your pain every couple of hours on a scale of 1 to 10, noting what you were doing or thinking when it occurred. When talking with your doctor, focus on the impact the pain has on your life (for example, it keeps you from exercising or going to work), not just the pain itself. Be specific when defining the pain in terms of the location, intensity, and when it is worst. Also list non-drug behaviors that help relieve the pain and improve function, including sleep, movement, diet, and stress management. Then bring that list with you when you see your health professional. It will make the visit more productive and help you both better understand your pain and how it impacts your life.

Managing

Managing chronic pain requires a holistic approach of medical and complementary therapies. A 2015 survey of 2,400 women with chronic pain found that 65 percent had tried exercise; 49 percent massage; 45 percent physical therapy; and 42 percent meditation for their pain. Many also tried yoga (27 percent), chiropractic (26 percent), acupuncture (20 percent), and medical marijuana (18 percent).

One area that is important and should not be neglected is how you think about your pain. One study found that women with negative thoughts about their pain—who magnify the pain in their minds—report more severe pain and are more likely to be taking prescription opioids than men with the same painful condition or women with lower levels of negative thinking.

This is where cognitive behavioral therapy can be particularly helpful. This form of short-term therapy teaches you to put your pain into the proper context and veer away from negative thoughts. Studies show it is quite effective at treating chronic pain and reducing catastrophizing, with or without other approaches.

One aspect that often gets ignored is the social aspect of pain. When you’re in pain, you tend to withdraw from your normal activities. This means withdrawing from people—and the people you love withdrawing from you. The isolation this creates can be devastating because social support is essential to health and healing. Indeed, without a social network, stress hormones surge, triggering the release of inflammatory chemicals and activating genes that can damage the mind and body. This includes slowing the healing process and preventing restorative sleep.

Another important component is self-care. Women are famous for pouring all their energy into caring for others and very little into caring for themselves. This is what happened to Carol, a 47-year-old patient of mine. She had been doing really well with her self-care—eating right, exercising, finding time to do the things she enjoyed and saying no to those she didn’t—but then her 10-year-old son was diagnosed with a mental health condition, and her self-care went out the window. She started gaining weight and stopped her stress management program Then she was in a car accident and hurt her neck. What should have been a short-term issue turned into a chronic pain condition.

Working together, we identified a safe, quiet place in her house where she could go to be alone and do whatever she liked. She called it “My Space.” Simply carving out that time for herself helped her see how she had lost her way, and gradually she was able to reintegrate the other lifestyle approaches she needed to return to a healthier—and pain-free—life.

Time to Journal

Journaling is a way of going on a retreat without leaving your home. It is a way to access and acknowledge past experiences that may be causing you pain and reintegrating them into your life so they become a part of you. It helps bring order to your deepest thoughts and fears and enables you to learn from the person who knows you best: you. Plus, you can go back and read what you’ve written to see how much progress you’ve made. Bottom line: Journaling provides a safe environment that enables you to face your traumas. When that happens, remarkable healing follows. Indeed, studies find that journaling can reduce pain, improve depression, and even lower markers of inflammation.

Journaling can also provide clues as to what makes your pain worse. For instance, one of my chronic pain patients, Mary, started keeping a journal in which she wrote down observations about what made her feel well and what did not. They didn’t have to be linked to her pain. It could be anything she saw that helped her feel better about herself—helped her feel happy and well. After two months of keeping this journal, she returned with several insights.

First, her back felt worse when she did not get enough sleep. Her normal pre-bed routine was eating a bowl of ice cream while watching the news, then reading on her iPad for 20 minutes before turning out the light. We talked about the stress that watching the news could trigger and the fact that the late-night snack could make for a less restful sleep as her body digested the food. Reading her tablet, with its “blue light,” is a known sleep deterrent.

So Mary began a sleep hygiene program that involved some calming tea before bed and five minutes of sitting quietly. When she got into bed, she read a real book before turning out the light and kept her phone and other electronics out of the bedroom. The result? Her sleep improved, leading to less pain on the days she followed this routine.

She realized other things through journaling as well. When she did her stretching and physical therapy exercises, she definitely felt better. But she had been doing them sporadically. After seeing the pattern, she made them a priority first thing in the morning. She also learned something else: On the anniversary of her father’s death, she felt excruciating pain. “Maybe I haven’t truly dealt with his death,” she said to me. So she started therapy to explore that issue.

My point is that the act of writing things down—with a pen and paper, not a phone or computer—can help you see the influences of your current and past life on your chronic pain.

Conclusion

Pain is the most common reason for doctor visits. And yet it is one of the most challenging medical conditions to treat, in part because it is so subjective and individualized. You and your friend might have the exact same diagnosis and yet feel the pain in completely different ways. That’s why it’s so important to remember that your pain is real and that you deserve the right treatment.

Finding the right combination of approaches to manage and reduce your pain can be a frustrating process. So I encourage you to be patient and to refuse to allow anyone to dismiss your pain. I also urge you to seek help from a variety of practitioners—both medical and complementary—in your search for pain relief and to take a whole person approach.

While they may not be able to completely cure your pain, the right mix of treatment and support, together with your commitment to doing your part, should definitely be able to reduce the frequency and severity of pain and give you back a better quality of life.

References

- Amandusson A, Blomqvist A. Estrogenic influences in pain processing. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34(4):329-349.

- American Massage Therapy Association. Consumer Views & Use of Massage Therapy. 2017; www.amtamassage.org/research/ Consumer-Survey-Fact-Sheets.html. Accessed June 7, 2017.

- Aubrun F, Salvi N, Coriat P, Riou B. Sex- and age-related differences in morphine requirements for postoperative pain relief. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(1):156-160.

- Back SE, Payne RL, Wahlquist AH, et al. Comparative profiles of men and women with opioid dependence: results from a national multisite effectiveness trial. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011 Sep;37(5):313-23. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596982. PMID: 21854273; PMCID: PMC3164783.

- Bijur PE, Esses D, Birnbaum A, Chang AK, Schechter C, Gallagher EJ. Response to morphine in male and female patients: analgesia and adverse events. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(3):192-198.

- Bonapace J, Gagne GP, Chaillet N, Gagnon R, Hebert E, Buckley S. No. 355-Physiologic Basis of Pain in Labour and Delivery: An Evidence-Based Approach to its Management. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40(2):227-245.

- Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(3 Suppl):S39-52.

- Centers for Disease and Control. Drug overdose deaths in the United States continue to increase in 2015. 2017; www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Multiple cause of death 1999-2020. Atlanta, GA: CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain: Recommendations. 2017 www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription Painkiller Overdoses: A Growing Epidemic, Especially Among Women. 2013; www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/prescriptionpainkilleroverdoses/index.html. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- Chen Esther H, Shofer Frances S, Dean Anthony J, et al. Gender Disparity in Analgesic Treatment of Emergency Department

Patients with Acute Abdominal Pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(5):414-418. - Chen Q, Larochelle MR, Weaver DT, et al. Prevention of prescription opioid misuse and projected overdose deaths in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Feb 1;2(2):e187621. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7621. PMID: 30707224; PMCID: PMC6415966.

- Chou R, Ballantyne J, Fanciullo G, Fine P, Miaskowski C. Research gaps on use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain: findings from a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2009;10(2):147-159.

- Craft RM, Mogil JS, Aloisi AM. Sex differences in pain and analgesia: the role of gonadal hormones. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(5):397-411.

- Fricton J, Gatchel RJ, Lawson KL, Whitebird R. Transformative Care for Chronic Pain and Addiction. Practical Pain Management. October 2, 2017. www.practicalpainmanagement.com/treatments/psychological/transformative-care-chronic-painaddiction.

- Gear RW, Miaskowski C, Gordon NC, Paul SM, Heller PH, Levine JD. Kappa-opioids produce significantly greater analgesia in women than in men. Nat Med. 1996;2(11):1248-1250.

- Gijsbers K, Nicholson F. Experimental pain thresholds influenced by sex of experimenter. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;101(3):803-807.

- Gomez-Pomar E, Finnegan LP. The Epidemic of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, Historical References of Its’ Origins, Assessment, and Management. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2018;6:33.

- Hinds NM, Wojtas ID, Gallagher CA, Corbett CM, Manvich DF. Effects of sex and estrous cycle on intravenous oxycodone self-administration and the reinstatement of oxycodone-seeking behavior in rats. Front Behav Neurosci. 2023 Jul 3;17:1143373. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1143373. PMID: 37465001; PMCID:PMC10350507.

- Hirschtritt ME, Delucchi KL, Olfson M. Outpatient, combined use of opioid and benzodiazepine medications in the United States, 1993-2014. Prev Med Rep. 2017 Dec 21;9:49-54. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.12.010. PMID: 29340270; PMCID: PMC5766756.

- Hoffman DE, Tarzian A. The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias Against Women in the Treatment of Pain. J Law Med Ethics. 2001;29(1):13-27.

- Huntington A, Gilmour JA. A life shaped by pain: women and endometriosis. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(9):1124-1132.

- Hurley RW, Adams MC. Sex, gender, and pain: an overview of a complex field. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(1):309-317.

- Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. 2011.

- Ivković N, Racic M, Lecic R, et al. Relationship Between Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders and Estrogen Levels in Women With Different Menstrual Status. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2018; Epub ahead of print.

- Jablonska B, Soares JJ, Sundin O. Pain among women: associations with socio-economic and work conditions. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(5):435-447.

- Koopman C, Ismailji T, Holmes D, Classen CC, Palesh O, Wales T. The effects of expressive writing on pain, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in survivors of intimate partner violence. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(2):211-221.

- Kozinoga M, Majchrzycki M, Piotrowska S. Low back pain in women before and after menopause. Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review. 2015;14(3):203-207.

- Majeed MH, Sudak DM. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain-One Therapeutic Approach for the Opioid Epidemic. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(6):409-414.

- Martin BI, Gerkovich MM, Deyo RA, et al. The association of complementary and alternative medicine use and health care expenditures for back and neck problems. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1029-1036.

- Martin VT, Pavlovic J, Fanning KM, Buse DC, Reed ML, Lipton RB. Perimenopause and Menopause Are Associated With High

Frequency Headache in Women With Migraine: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache. 2016;56(2):292-305. - McDade TW, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Psychosocial and behavioral predictors of inflammation in middle-aged and older adults: the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(3):376-381.

- McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015 Jan;48(1):1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.08.004. Epub 2014 Aug 28. PMID: 25239857; PMCID: PMC4250400.

- Meriggiola MC, Nanni M, Bachiocco V, Vodo S, Aloisi AM. Menopause affects pain depending on pain type and characteristics. Menopause. 2012;19(5):517-523.

- Mogil JS, Bailey AL. Sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia. Prog Brain Res. 2010;186:141-157.

- Monaco K. www.medpagetoday.com/meetingcoverage/nams/68527. Menopause May Be Risk Period for Chronic Pain, Opioid Use. October 13, 2017. www.medpagetoday.com/meetingcoverage/nams/68527. Accessed March 25, 2018.

- Morley S, Williams A, Hussain S. Estimating the clinical effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy in the clinic: evaluation of a CBT informed pain management programme. Pain. 2008;137(3):670-680.

- Nahin RL. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J Pain. 2015;16(8):769-780.

- National Bureau of Economic Research. The Bulletin on Health. The enduring impacts of oxycontin reformulation. Available at www.nber.org/bh-20202/enduring-impacts-oxycontinreformulation. Accessed March 20, 2025.

- National Pain Report, For Grace. Women in Pain Survey. 2015; www.surveymonkey.com/results/SM-P5J5P29L. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- Nault T, Gupta P, Ehlert M, et al. Does a history of bullying and abuse predict lower urinary tract symptoms, chronic pain, and sexual dysfunction? Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48(11):1783-1788.

- Office on Women’s Health. Final Report: Opioid Use, Misuse, and Overdose in Women. July 2017 www.womenshealth.gov/files/documents/final-report- opioid-508.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Pepe L, Milani R, Di Trani M, Di Folco G, Lanna V, Solano L. A more global approach to musculoskeletal pain: expressive writing as an effective adjunct to physiotherapy. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19(6):687-697.

- Quintiles IMS. An Analysis of the Impact of Opioid Overprescribing in America. Pacira Pharmaceuticals; September 2017 www.

planagainstpain.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/PlanAgainstPain_USND.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2018. - Redwine LS, Henry BL, Pung MA, et al. Pilot Randomized Study of a Gratitude Journaling Intervention on Heart Rate Variability and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients With Stage B Heart Failure. Psychosom Med. 2016;78(6):667-676.

- Relief for your aching back: what worked for our readers.Consum Rep. March 17, 2017. www.consumerreports.org/cro/2013/01/relief-for-your-aching-back/index.htm. Accessed June 12, 2017.

- Sanlorenzo LA, Stark AR, Patrick SW. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30(2):182- 186.

- Sartor CE, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J. Rate of progression from first use to dependence on cocaine or opioids: a crosssubstance examination of associated demographic, psychiatric, and childhood risk factors. Addict Behav. 2014 Feb;39(2):473-9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.021. Epub 2013 Oct 18. PMID: 24238782; PMCID: PMC3855905.

- Schutze R, Rees C, Smith A, Slater H, Campbell JM, O’Sullivan P. How Can We Best Reduce Pain Catastrophizing in Adults With Chronic Noncancer Pain? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2018;19(3):233-256.

- Sharifzadeh Y, Kao MC, Sturgeon JA, Rico TJ, Mackey S, Darnall BD. Pain Catastrophizing Moderates Relationships between Pain Intensity and Opioid Prescription: Nonlinear Sex Differences Revealed Using a Learning Health System. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(1):136-146.

- Smith CA, Collins CT, Cyna AM, Crowther CA. Complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006(4):Cd003521.

- Smith CA, Levett KM, Collins CT, Crowther CA. Relaxation techniques for pain management in labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011(12):Cd009514.

- Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, Winzenberg TM, Hosmer D, Jones G. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(9):769-781.

- Trivedi MH. The Link Between Depression and Physical Symptoms. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(suppl1):12-16.

- Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Veehof MM, Schreurs KM. Internet-based guided self-help intervention for chronic pain based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med. 2015;38(1):66-80.

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Oxycodone. Available at www.dea.gov/factsheets/oxycodone. Accessed March 21, 2025.

- Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1444-1453.

- Vincent K, Tracey I. Hormones and their Interaction with the Pain Experience. Reviews in Pain. 2008;2(2):20-24.

Contributors

The following individuals provided guidance in the creation of the first edition of this paper, but the product is the work of the author, who recently did an update in 2025, and is not necessarily a reflection of the contributors’, nor their organizations’ opinions.

Maggie Buckley, MBA

Board of Directors, The Pain Community

Buckley has been a volunteer patient advocate for more than 20 years while living with the chronic pain condition Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

Cynthia Toussaint

Founder and Spokesperson, For Grace

(forgrace.org)

Toussaint has been a leading voice for women living with chronic pain since 2002. She has been living with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome and several other auto-immune conditions for 35 years.

Dr. James Fricton

Dr. Fricton had post-doctoral training in pain at UCLA and has devoted his career to patient care and research in temporomandibular and orofacial pain disorders. He also serves as a Professor in the Department of Diagnostic and Surgical Sciences at the School of Dentistry at the University of Minnesota. Dr. Fricton has published and lectured extensively and is the author of TMJ and Craniofacial Pain: Diagnosis and Management, Myofacial Pain and Fibromyalgia, and Advances in Orofacial Pain and TMJ Disorders. He currently sees patients at the Minnesota Head & Neck Pain Clinic, whose mission is to provide high-quality, effective patient care for head and neck disorders through a multispecialty, interdisciplinary approach designed to reduce pain and improve function.

About the Author — Dr. Wayne Jonas

Wayne B. Jonas, MD, is a board-certified, practicing family physician, an expert in integrative health and whole person care delivery, and a widely published scientific investigator and author of the bestselling book How Healing Works. Additionally, Dr. Jonas is a retired Lieutenant Colonel in the Medical Corps of the United States Army.

Topics: Chronic Pain | Trauma | Women