Welcome to the latest essay in our “On Healing” series, where Dr. Wayne Jonas explores whole person care and the deeper dimensions of healing.

“Doc, is acupuncture any good, or is it all just placebo?”

That was the question my patient Bill, a retired Navy master chief who had battled degenerative disc disease and back pain for 15 years asked as I entered the room. He had tried almost everything: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, steroid injections, two spine surgeries, antidepressants, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation units, physical therapy, and chiropractic adjustments. He was a veteran who had fought and won many battles in his life, but he was not winning this one.

How could I give him a good evidence-based answer? In modern health care, evidence is the foundation for decisions at every level, from national policy to the choices clinicians and patients make when they are sick. Yet it can be surprisingly hard to agree on what constitutes “good” evidence.

What is “Good” Evidence?

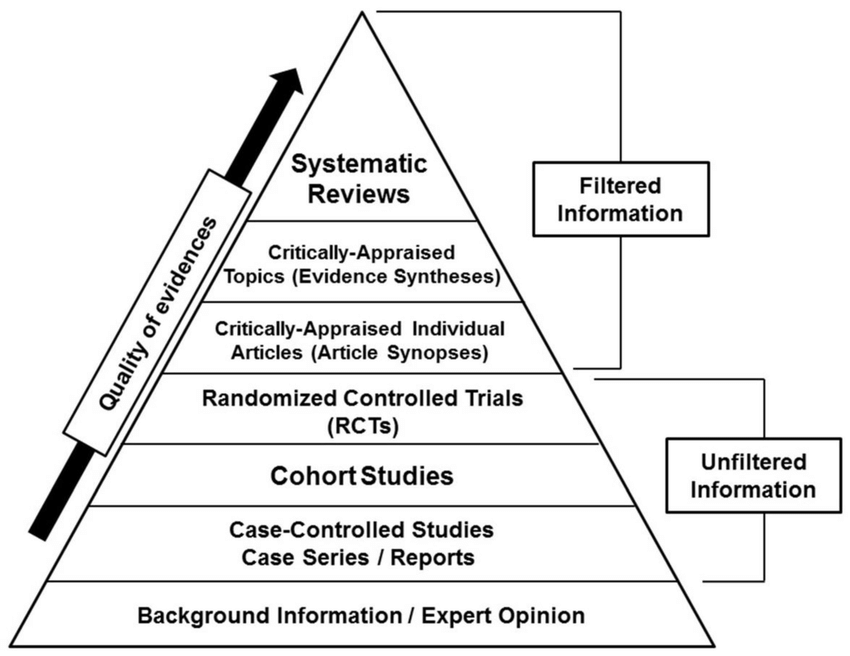

The term “evidence-based medicine” (EBM), now a core aspect of clinical practice and policy decisions, was first coined in the early 1990s.¹ Before that, medical decisions depended heavily on expert opinion, clinical experience, and the weight of authority. The goal of EBM was to bring the standards of clinical science, particularly randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews, to the top of decision-making.

RCTs are most valuable in determining the best treatments for relatively short-term problems where single treatments can be matched directly against outcomes and compared to placebo or standard of care groups, such as testing a new drug against infections or the impact of tumor removal on survival in cancer. They are usually based on studies in highly selected populations conducted over relatively short periods. However, for complex chronic conditions, which are affected by a multitude of factors and last a long time, RCTs alone often do not offer the most valuable evidence.

Patients with complex chronic conditions, like Bill, benefit from wider perspectives. Other methods, such as health services research, observational studies, and patient narratives, while considered less valuable from an EBM perspective, can help us understand a treatment’s broad effectiveness, relevance, feasibility, and personal impact in treating complex chronic conditions. They provide good evidence for certain types of decision-making.

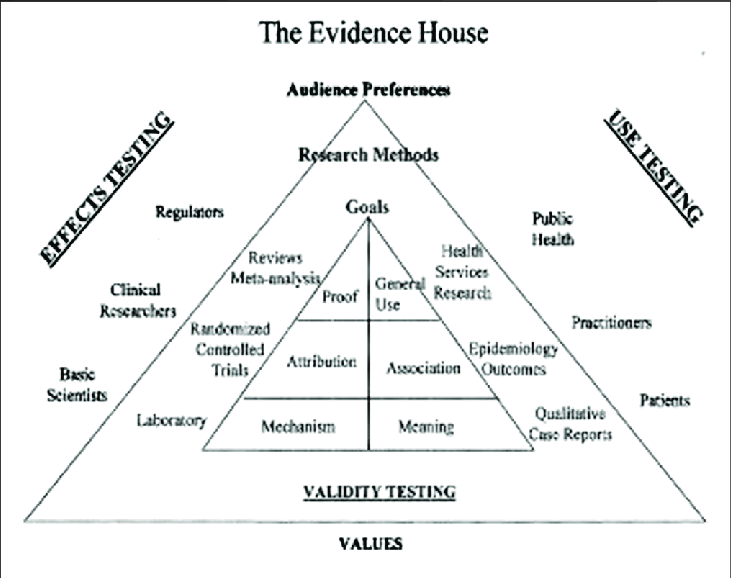

Instead of a hierarchy (with large RCTs and systematic reviews at the top), I often picture the medical evidence landscape as a house with two sides, or wings, which I call the Evidence House.² On one side are investigations that aim to isolate specific attributional effects of focused treatments. These involve laboratory studies, RCTs, and systematic reviews—types of evidence focused on mechanisms and efficacy.

In the other wing of the Evidence House are types of research that aim to discover the magnitude and relevance of effects in the real, complex world. This research involves methods such as health services research, cohort or observational studies, and qualitative research. These methods reveal the nuances of context, feasibility, and what matters in real lives—often called “effectiveness.”

A truly livable Evidence House that provides good evidence across the decision landscape needs data from both sides and all rooms of the house. If we overinvest in one wing of the house or in just one room, as EBM currently does, we shortchange not only science but also patients.

How to Help Patients

How does this relate to Bill’s question about acupuncture? Research shows acupuncture can offer relief for some chronic pain conditions, but there’s an ongoing debate about separating its effects from what’s called the placebo effect or what I like to call the meaning response.3

The placebo or meaning response isn’t just in your head—it flows from expectation, ritual, patient-provider relationship, conditioned learning, and context. These factors can spark genuine physiological change and often account for a significant part of any treatment’s effectiveness.4

For patients like Bill, the essential question may not be, “Have RCTs shown that acupuncture works better on average than placebo for back pain?” but rather “Is acupuncture safe to try? Has it helped patients like me? Could it affect the outcomes that matter most to me—pain relief, my ability to play with my grandchildren, my sleep, my mood, and sense of well-being? And to what extent and for what cost? Does it help 20% of patients like me or 80%?” Most of these questions have not been subjected to RCTs.

To help patients with complex, chronic conditions, we must draw on evidence from both wings of the house: RCT research and other studies that examine the realities of the situation and experience of the particular person in front of us.

Yet even with promising evidence, practical barriers remain—most notably, payment and insurance coverage. Accessing integrative approaches like acupuncture or massage depends not only on clinical data but also on whether insurers consider them cost-effective and necessary. When they consider only “good” evidence studies on costs using RCTs from narrow populations—evidence drawn from the top of the current evidence hierarchy—they find little evidence indeed.5

As clinicians and patients navigate these choices, it’s important to look for coverage opportunities and to recognize that out-of-pocket payment may be required. What payers value—cost, coverage criteria—can be quite different from what patients seek: healing, safety, access, and the potential for personalized care. This was the case for my patient Bill. Despite the lack of “good” evidence for acupuncture being better than placebo for back pain, he chose to pursue acupuncture to see if it helped. Along with other forms of support for his stress and sleep, it did help him get back on his feet and accomplish what mattered to him in life. He had less pain, and he was able to use less medication, both of which improved his quality of life and allowed him to play with his grandchildren. Thus, the non-RCT evidence turned out to be the most important type of evidence for him.

Making these realities part of the conversation is an essential aspect of honoring evidence in practice and deciding what is “good.” Good evidence is made up not only of properly collected and analyzed data but also of how useful it is for various decision-makers—especially patients. In addition, working around authorization and reimbursement and finding budget-friendly options for care are important parts of those decisions.

In my experience, the best healing happens when we integrate scientific rigor with personal relevance. This requires us to have a deep respect for the patient’s perspective. Evidence is more than what can be measured quantitatively—it is also what can be meaningfully experienced, understood, and accessed. Balancing science, personal values, and access is the key to finding and using “good” evidence.

References

- Zimerman, AL. Evidence-based medicine: A short history of a modern medical movement. AMA Journal of Ethics. 2013;15(1):71-76. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.1.mhst1-130

- Jonas WB. The evidence house: How to build an inclusive base for complementary medicine. West J Med. 2001;175(2):79-80. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1071485/

- Moerman DE, Jonas WB. Deconstructing the placebo effect and finding the meaning response. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Mar 19;136(6):471-6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-6-200203190-00011

- Colloca, L, Noel, J, Franklin, PD, Seneviratne, C. Placebo Effects Through the Lens of Translational Research. Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Rizzo RR, Cashin AG, Wand BM, et al. Non‐pharmacological and non‐surgical treatments for low back pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2025(3). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014691.pub2

Photo by Vladislav Babienko on Unsplash