You only think you’re alone.

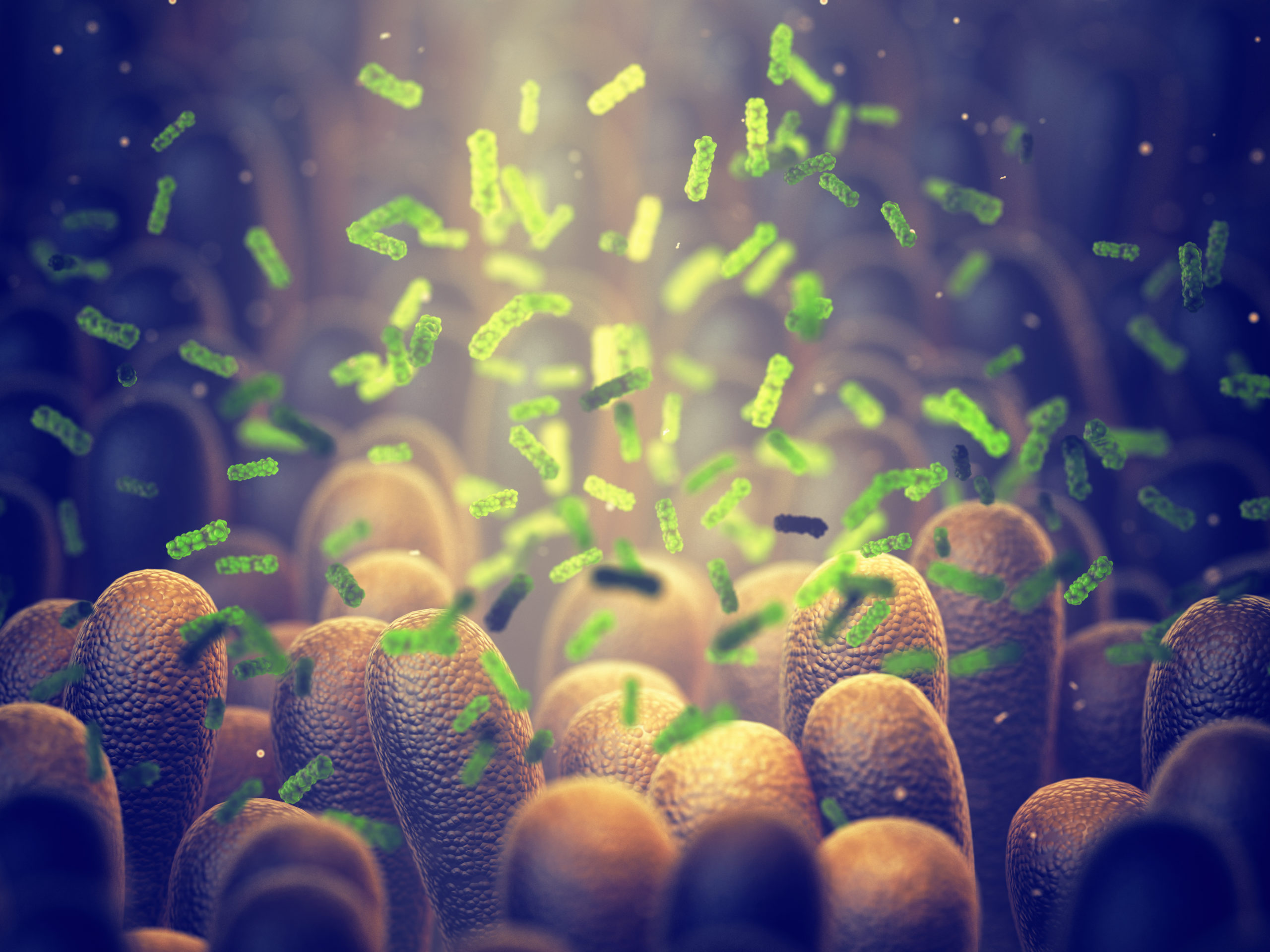

In fact, your body – inside and out – is teeming with life. Each of us has approximately 1 trillion microorganisms in our bodies and on our skin. You spend each day as part of a giant community of other organisms, each with its own DNA.[i]

Your body’s microbiomes

Before this creeps you out completely, remember that you’ve probably heard of the gut microbiome. This is the collection of “good” bacteria and other microscopic organisms that helps your digestive system do its job, from one end to the other. When it’s disrupted, for example by taking antibiotics, you may notice a change.

Your skin has a microbiome too, which is why the latest skin care trend is probiotic beauty. The female reproductive system has a specific microbiome that changes during pregnancy.[ii] (Pregnancy also changes the microbiome in your mouth, known as the oral microbiome.[iii]) Researchers are investigating other body systems to learn if they have their own microbiomes.

Microbiomes in the environment

All buildings have an “indoor microbiome” made up of the organisms that live there, plus non-living material such as particles of dirt or pet hair.[iv] Your home, office, school, and the stores where you shop have individual microbiomes. Your mobile phone has its own microbiome.

Animals, birds, and insects have their own microbiomes as well, and they can be disrupted just like ours by illness, medications, or pollutants. For example, changes to the gut microbiomes of honeybees are one reason for the decline in these insects’ population. The changes are caused by the herbicide glyphosate, aka Roundup.[v] This common weed killer interferes with the bees’ ability to navigate their normal routes from flowers to hives. Other chemicals, such as those found in household cleaners, can affect the microbiome too.

Research on the microbiome

The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) was a 10-year effort of the US National Institutes of Health that aimed to learn about the microbes that populate us. From 2007-2017, research from the HMP led to more than 650 publications.[vi]

Among other fascinating things, HMP researchers created a “map” of the microbiome for healthy adults. They also learned that the microbiota, or organisms of the microbiome, are essential contributors to human body processes such as food digestion, inflammation, and immunity.

Today, doctors are using microbes from healthy microbiomes to treat disease. A fecal transplant is just what it sounds like: giving a small amount of fecal, or stool, material from a healthy person to someone who lacks healthy gut microbes or has too few of them. (The fecal material is prepared beforehand in a pill, enema, or other form that is safe to use.) This type of treatment can be used for many conditions including infections, cancer, and potentially inflammatory bowel disease, though larger studies are needed.[vii],[viii]

What does it mean for you?

Your microbiome is like no one else’s. You can be identified by your microbiome, at least for a certain period of time.[ix] And those microscopic organisms? They have their own DNA, so their genetic makeup is a potential target for new treatments such as enhancing cancer drugs and much more.

You can support a healthy microbiome in several ways.

Eat foods that support gut health. Prebiotic foods are foods that feed a healthy microbiome. These are foods such as oatmeal, bananas, leeks, and lentils that help the microbiome flourish by providing material for it to break down, or “eat.” A low-fiber diet that contains a lot of processed food products does not feed these organisms as well.

The digestive system and brain are intimately linked, so supporting the gut microbiome can also support mental and emotional well-being.[x] Beans and fermented foods are a good source of health food for the gut.

Researchers are investigating specific dietary regimes for diseases of the immune system such as multiple sclerosis, irritable bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and cancer.[xi] However, even in these cases, no plan works the same way for everyone because each microbiome is unique. If you do have a chronic condition, try searching for “microbiome health and [condition]” to learn if there are specific ways to support your healing with food.

Don’t disturb the skin microbiome too much. Washing your hands often, using antibacterial soaps and sanitizers, and ironically, using a lot of skin-care products and cosmetics can disrupt the delicate balance of your skin’s microbiome.[xii] It can be challenging to avoid this when you are also trying to prevent COVID-19 infection, colds, and flu, as washing your hands is one of the best ways to prevent spreading infections. Using plain (not antibacterial) soap is a good solution in non-medical settings to decrease the spread of germs and maintain the good bacteria on your skin.

While “probiotic beauty” is a hot trend at the moment, it’s a good idea to talk with a health care provider such as a dermatologist about whether these products will really help your skin or treat skin conditions. They can be expensive and may or may not work well with your skin’s microbiome.

Medical researchers are studying transplants of bacteria to help treat allergies affecting the skin (atopic dermatitis), dietary approaches for healing eczema, and more.[xiii] Further understanding of the skin microbiome will likely lead to new treatments that work with your body.

Respect the oral microbiome. The biofilm called plaque that develops on your teeth is home to many microorganisms. When it is disrupted, such as by a tooth cleaning or dental treatment, bacteria are released into the rest of your body. (This is why some people need antibiotics before dental work.)

It’s boring, but cleaning your teeth regularly, including flossing; staying well hydrated; eating a healthful diet; avoiding smoking and too much alcohol; and avoiding stress are keys to maintaining a healthy oral microbiome.[xiv] Talk to your dentist about using alcohol-free mouthwash, which targets more bad bacteria than good.

Learn more about the microbiome

The microbiome of just one human is impressively large. We’ve provided you with some sources to learn more about how minding your microbiome can lead to better health.

- Everything You Need to Know About Fecal Transplants

- 15 Tips to Boost Your Gut Microbiome

- Ganguly P. Microbes in us and their role in human health and disease. NIH National Human Genome Research Institute. May 29, 2019.

- Gut Microbiome and Mental Health

- Learning about gut health: Facebook Live Interview with Dr. Emeran Mayer

- I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life, by Ed Yong

References

[i] Davenport ER, Sanders JG, Song, SJ, et al. The human microbiome in evolution. BMC Biol 2017 (15):127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-017-0454-7

[ii] Nunn KL, Witkin SS, Schneider GM, et al. Changes in the vaginal microbiome during the pregnancy to postpartum transition. Reprod Sci 2021;28(7):1996-2005. doi:10.1007/s43032-020-00438-6

[iii] Ye C, Kapila Y. Oral microbiome shifts during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Hormonal and Immunologic changes at play. Periodontol 2000 2021;87(1):276-281. doi:10.1111/prd.12

[iv] United States Environmental Protection Agency. The indoor microbiome. Last updated April 14, 2022. Available at https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/indoor-microbiome. Accessed September 8, 2022.

[v] Motta EVS, Mak M, De Jong TK, et al. Oral or topical exposure to glyphosate in herbicide formulation impacts the gut microbiota and survival rates of honey bees. Appl Environ Microbiol 2020;86(18):e01150-20. Published 2020 Sep 1. doi:10.1128/AEM.01150-20

[vi] National Institutes of Health Office of Strategic Coordination – The Common Fund. The Human Microbiome Project. Last reviewed August 20, 2020. Available at https://commonfund.nih.gov/hmp/. Accessed September 8, 2022.

[vii] Youngster I, Russell GH, Pindar C, Ziv-Baran T, Sauk J, Hohmann EL. Oral, capsulized, frozen fecal microbiota transplantation for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA 2014;312(17):1772–1778. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13875

[viii] Claytor JD, El-Nachef N. Fecal microbial transplant for inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2020;23(5):355-360. doi:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000676

[ix] Pesheva, E. Microbial fingerprinting. Harvard Medical News and Research, August 14, 2019. Available at https://hms.harvard.edu/news/microbial-fingerprinting. Accessed September 8, 2022.

[x] Tenchov, R. Gut microbiome and mental health: The gut feeling that links to depression and anxiety. CAS: A division of the American Chemical Society. Available at https://www.cas.org/resources/blog/gut-microbiome-mental-health. Accessed September 8, 2022.

[xi] Wolter M, Grant ET, Boudaud M, et al. Leveraging diet to engineer the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18(12):885-902. doi:10.1038/s41575-021-00512-7

[xii] Dréno B, Araviiskaia E, Berardesca E, et al. Microbiome in healthy skin, update for dermatologists. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016;30(12):2038-2047. doi:10.1111/jdv.13965

[xiii] Hendricks AJ, Mills BW, Shi VY. Skin bacterial transplant in atopic dermatitis: Knowns, unknowns and emerging trends. J Dermatol Sci 2019;95(2):56-61. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.07.001

[xiv] Kilian M, Chapple I, Hannig M, et al. The oral microbiome – an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br Dent J 2016;221:657–666. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.865

Take Your Health Into Your Own Hands

Drawing on 40 years of research and patient care, Dr. Wayne Jonas explains how 80 percent of healing occurs organically and how to activate the healing process.